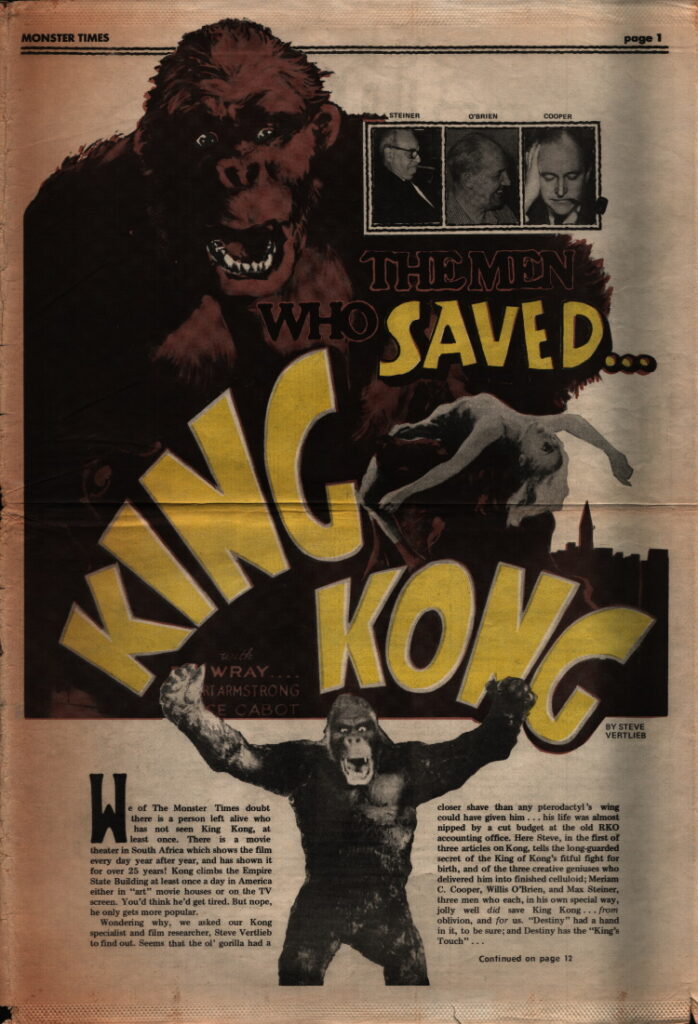

We of The Monster Times doubt there is a person left alive who has not seen King Kong, at least once. There is a movie theater in South Africa which shows the film every day year after year, and has shown it for over 25 years! Kong climbs the Empire State Building at least once a day in America either in “art” movie houses or on the TV screen. You’d think he’d get tired. But nope, he only gets more popular.

Wondering why, we asked our Kong specialist and film researcher, Steve Vertlieb to find out. Seems that the ol’ gorilla had a closer shave than any pterodactyl’s wing could have given him… his life was almost nipped by a cut budget at the old RKO accounting office. Here Steve, in the first of three articles on Kong, tells the long-guarded secret of the King of Kong’s fitful fight for birth, and of the three creative geniuses who delivered him into finished celluloid; Merian C. Cooper, Willis O’Brien, and Max Steiner, three men who each, in his own special way, jolly well did save King Kong… from oblivion, and for us. “Destiny” had a hand in it, to be sure; and Destiny has the “King’s Touch”…

There is a place, a vault of dreams where never realized plans and almost forgotten projects sit, alone and lost, on a dusty and cluttered shelf accumulating endless, endless time. Some were films that never came to be, and while many of these abandoned productions must be mourned over and lamented, there has been an occasional instance when the decision for change has been the right one, the proper one, a choice that forever shaped the history of motion pictures.

In 1940, the world was deprived of a film called “The War Eagle” that was to have been made by M.G.M. Had it been filmed the chances are great that the picture would have emerged a fantasy classic, for it was the project of General Merian C. Cooper, the man responsible for bringing to the screen the single most impressive fantasy film of all time.

“The War Eagle” was in its early planning stages when “Coop” returned to active military service, thereby terminating its production. A costly endeavor, the picture would have painted the fantastic portrait of a race of cavemen astride giant, prehistoric birds, who attempt to conquer modern-day New York?

Does the basic premise of this plot sound familiar? It should, for this would have been the third time that a film based upon that plot had been produced.

The first film to have employed prehistoric creatures in a modern setting was First National’s daring version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World” released in 1925 and starring Wallace Beery, Lewis Stone and Bessie Love. However, it was the second attempt at filming this theme that truly captured the imagination of the theatre-going world and inspired unparalleled excitement for attending audiences nearly forty years after its original release.

the film that almost wasn’t

The film was, of course, “King Kong” and it was largely the end result of an idea formed years earlier in the mind of Merian Cooper, the creative genius behind some of the most exciting and visually impressive fare in the past fifty years. Many men with considerable talent helped to form what would have become the final version of “King Kong” but throughout its enumerable growing pains there seemed to be only one man who remained faithfully behind the project from its modest beginnings. Cooper, alone, persisted in his faith that “Kong” would one day become a reality, and were it not for his far-sighted efforts on behalf of the world’s most celebrated gorilla, “King Kong” would have turned out a very different film, indeed.

“King Kong” began to form in Cooper’s mind as early as 1930, when he completed the first “treatment” of the story. From the beginning he had envisioned a modernistic re-telling of “The Beauty And The Beast” in which a giant gorilla would be transported from his home in a primitive jungle to the more polished skyscraper jungles of New York. There he would meet his end atop the tower of the awesome Empire State Building, fighting for his right to existence against civilization’s bullet-spewing Pterodactyls.

no tin lizards, they!

Cooper’s fascination with apes stemmed from his days in Africa shooting footage, with his close friend and associate Ernest B. Schoedsack, for their silent adventure classic, “Four Feathers”, but the force that triggered his inspiration for “Kong” would seem to have been the publication of “The Dragon Lizards of Komodo”, the true story of nine-foot carnivorous lizards on Komodo Island in the East Indies.

The book was written by a friend of Cooper’s, W. Douglas Burden, a director at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, and set Cooper thinking of how easy it would be to utilize these lizards within the framework of his film. He would take a camera crew to Africa once again and shoot footage of a normal gorilla, and then transport that animal to the island of Komodo for a fight with an actual dragon. Later at the studio he could always enlarge both of the animals on film to make them appear abnormally large.

Cooper consulted with Burden about a name to call his huge protagonist. “Coop” seemed to have an affinity for names of one syllable in his previous productions, and the more unusual sounding they were the happier he would be. As all of the native dialogue used in the final film was to be authentic, he finally decided upon using the islander’s word for gorilla which happened to be “KONG”. He added a title to his character to impress his power upon the audience and the simple result was King Gorilla, or as in the preferred translation, “King Kong.”

back-breaking backing back in broke-days

Now, the problem was to find studio backing-not an easy task in a depression. Famed film producer David O. Selznick and his brother, Myron, were in New York trying to raise money in hopes of beginning a new, independent production company that David would head. Cooper presented the idea to the Selznicks but they had their own problems at the time and “Kong” was just not ready for production yet. The moment had not yet arrived.

The year was 1931 and in September of that year David Selznick became executive vice president in charge of production at R.K.O. The studio had suffered through years of mismanagement and was on the verge of bankruptcy. Selznick was handed the enormous task of saving the company. One of his first official decisions was to call in his old friend, Merian Cooper, to assist him in cleaning up the mess. One of Cooper’s assignments was to evaluate projects either in, or planned for production that were held over from the previous regime. Decisions would be made then on whether or not they were worth continuing or if it would be financially wiser to simply scrap the projects and move ahead to newer, sounder adventures.

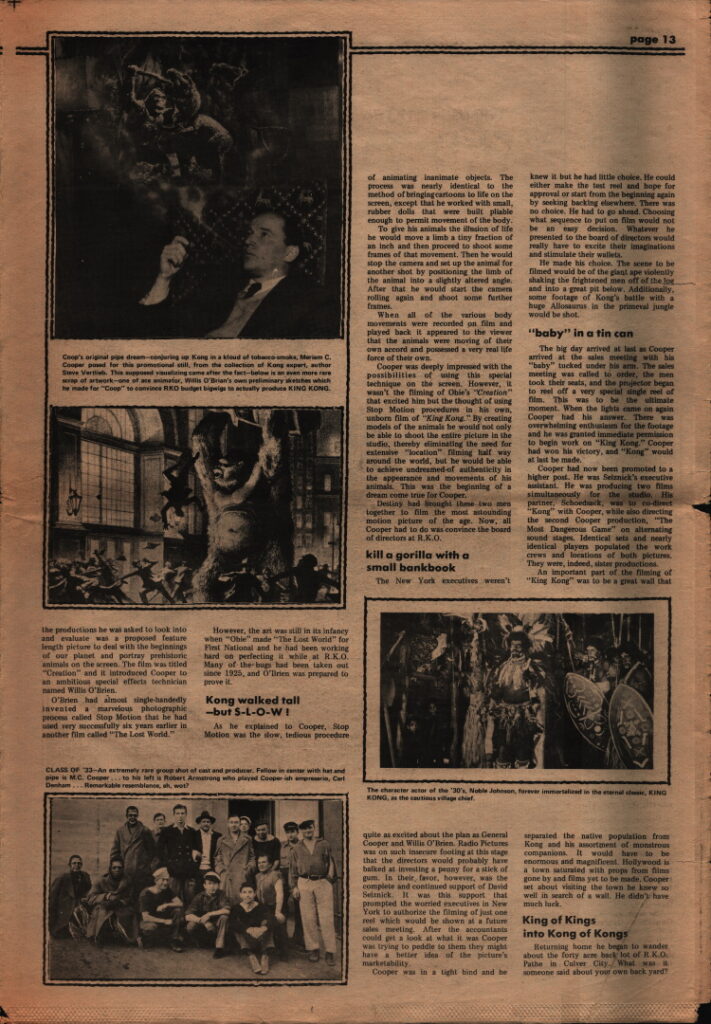

Here, fate stepped into the life of “Coop” and his pet project, for among the productions he was asked to look into and evaluate was a proposed feature-length picture to deal with the beginnings of our planet and portray prehistoric animals on the screen. The film was titled “Creation” and it introduced Cooper to an ambitious special effects technician named Willis O’Brien.

O’Brien had almost single-handedly invented a marvelous photographic process called Stop Motion that he had used very successfully six years earlier in another film called “The Lost World.”

However, the art was still in its infancy when “Obie” made “The Lost World” for First National and he had been working hard on perfecting it while at R.K.O. Many of the bugs had been taken out since 1925, and O’Brien was prepared to prove it.

Kong walked tall -but S-L-O-W!

As he explained to Cooper, Stop Motion was the slow, tedious procedure of animating inanimate objects. The process was nearly identical to the method of bringing cartoons to life on the screen, except that he worked with small, rubber dolls that were built pliable enough to permit movement of the body.

To give his animals the illusion of life he would move a limb a tiny fraction of an inch and then proceed to shoot some frames of that movement. Then he would stop the camera and set up the animal for another shot by positioning the limb of the animal into a slightly altered angle. After that he would start the camera rolling again and shoot some further frames.

When all of the various body movements were recorded on film and played back it appeared to the viewer that the animals were moving of their own accord and possessed a very real-life force of their own.

Cooper was deeply impressed with the possibilities of using this special technique on the screen. However, it wasn’t the filming of Obie’s “Creation” that excited him but the thought of using Stop Motion procedures in his own, unborn film of “King Kong.” By creating models of the animals he would not only be able to shoot the entire picture in the studio, thereby eliminating the need for extensive “location” filming halfway around the world, but he would be able to achieve undreamed-of authenticity in the appearance and movements of his animals. This was the beginning of a dream come true for Cooper.

Destiny had brought these two men together to film the most astounding motion picture of the age. Now, all Cooper had to do was convince the board of directors at R.K.O.

kill a gorilla with a small bankbook

The New York executives weren’t quite as excited about the plan as General Cooper and Willis O’Brien. Radio Pictures was on such insecure footing at this stage that the directors would probably have balked at investing a penny for a stick of gum. In their favor, however, was the complete and continued support of David Selznick. It was this support that prompted the worried executives in New York to authorize the filming of just one reel which would be shown at a future sales meeting. After the accountants could get a look at what it was Cooper was trying to peddle to them they might have a better idea of the picture’s marketability.

Cooper was in a tight bind and he knew it but he had little choice. He could either make the test reel and hope for approval or start from the beginning again by seeking backing elsewhere. There was no choice. He had to go ahead. Choosing what sequence to put on film would not be an easy decision. Whatever he presented to the board of directors would really have to excite their imaginations and stimulate their wallets.

He made his choice. The scene to be filmed would be of the giant ape violently shaking the frightened men off of the log and into a great pit below. Additionally, some footage of Kong’s battle with a huge Allosaurus in the primeval jungle would be shot.

“baby” in a tin can

The big day arrived at last as Cooper arrived at the sales meeting with his “baby” tucked under his arm. The sales meeting was called to order, the men took their seats, and the projector began to reel off a very special single reel of film. This was to be the ultimate moment. When the lights came on again Cooper had his answer. There was overwhelming enthusiasm for the footage and he was granted immediate permission to begin work on “King Kong.” Cooper had won his victory, and “Kong” would at last be made.

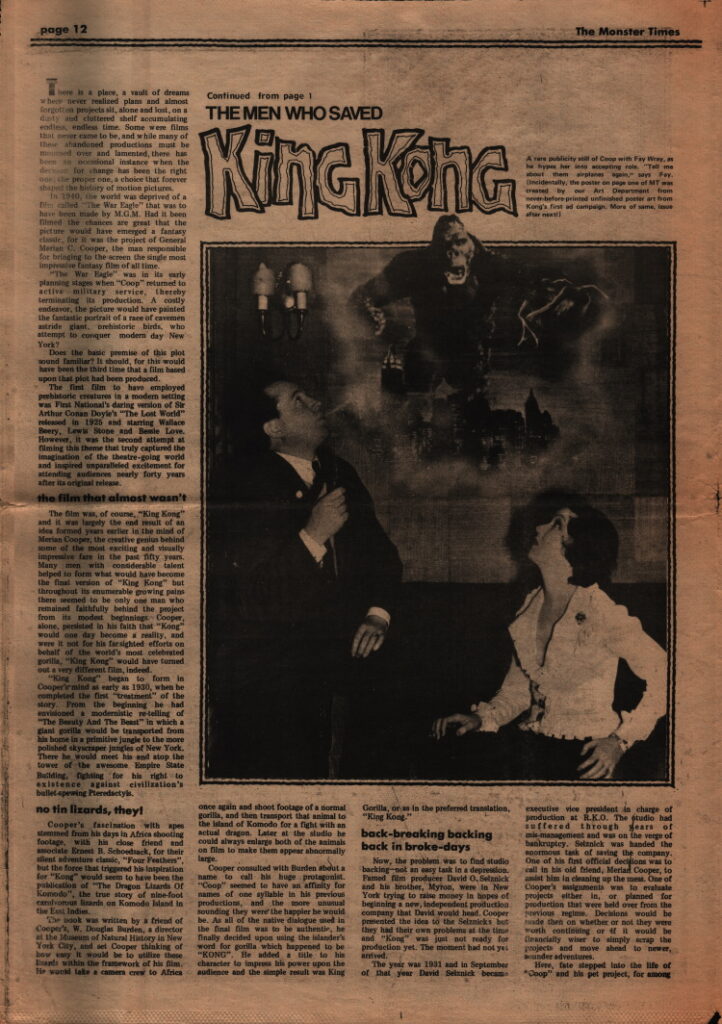

Cooper had now been promoted to a higher post. He was Selznick’s executive assistant. He was producing two films simultaneously for the studio. His partner, Schoedsack, was to co-direct “Kong” with Cooper, while also directing the second Cooper production, “The Most Dangerous Game” on alternating sound stages. Identical sets and nearly identical players populated the work crews and locations of both pictures. They were, indeed, sister productions.

An important part of the filming of “King Kong” was to be a great wall that separated the native population from Kong and his assortment of monstrous companions. It would have to be enormous and magnificent. Hollywood is a town saturated with props from films gone by and films yet to be made. Cooper set about visiting the town he knew so well in search of a wall. He didn’t have much luck.

King of Kings into Kong of Kongs

Returning home he began to wander about the forty-acre back lot of R.K.O. Pathe in Culver City. What was it someone said about your own backyard?

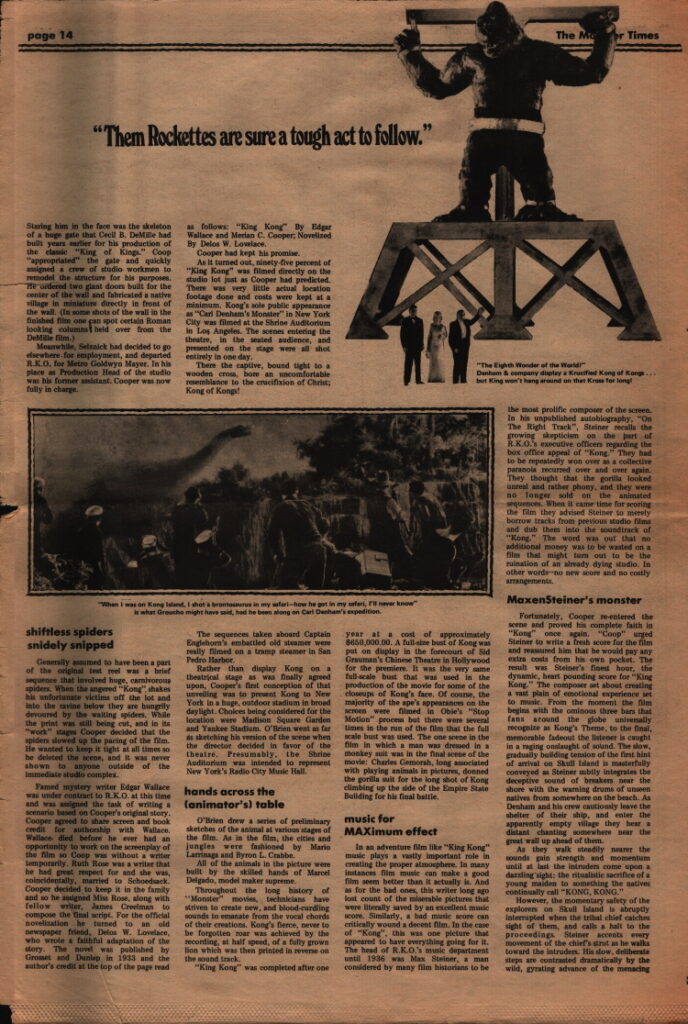

“Them Rockettes are sure a tough act to follow.”

Staring him in the face was the skeleton of a huge gate that Cecil B. DeMille had built years earlier for his production of the classic “King of Kings.” Coop “appropriated” the gate and quickly assigned a crew of studio workmen to remodel the structure for his purposes. He ordered two giant doors built for the center of the wall and fabricated a native village in miniature directly in front of the wall. (In some shots of the wall in the finished film one can spot certain Roman-looking columns held over from the DeMille film.)

Meanwhile, Selznick had decided to go elsewhere for employment, and departed R.K.O. for Metro Goldwyn Mayer. In his place as Production Head of the studio was his former assistant. Cooper was now fully in charge.

shiftless spiders snidely snipped

Generally assumed to have been a part of the original test reel was a brief sequence that involved huge, carnivorous spiders. When the angered “Kong” shakes his unfortunate victims off the lot and into the ravine below they are hungrily devoured by the waiting spiders. While the print was still being cut, and in its “work” stages Cooper decided that the spiders slowed up the pacing of the film. He wanted to keep it tight at all times so he deleted the scene, and it was never shown to anyone outside of the immediate studio complex.

Famed mystery writer Edgar Wallace was under contract to R.K.O. at this time and was assigned the task of writing a scenario based on Cooper’s original story. Cooper agreed to share screen and book credit for authorship with Wallace. Wallace died before he ever had an opportunity to work on the screenplay of the film so Coop was without a writer temporarily. Ruth Rose was a writer that he had great respect for and she was, coincidentally, married to Schoedsack. Cooper decided to keep it in the family and so he assigned Miss Rose, along with fellow writer, James Creelman to compose the final script. For the official novelization he turned to an old newspaper friend, Delos W. Lovelace, who wrote a faithful adaptation of the story. The novel was published by Grosset and Dunlap in 1933 and the author’s credit at the top of the page read as follows: “King Kong” By Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper; Novelized By Delos W. Lovelace.

Cooper had kept his promise.

As it turned out, ninety-five percent of “King Kong” was filmed directly on the studio lot just as Cooper had predicted. There was very little actual location footage done and costs were kept at a minimum. Kong’s sole public appearance as “Carl Denham’s Monster” in New York City was filmed at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. The scenes entering the theatre, in the seated audience, and presented on the stage were all shot entirely in one day.

There the captive, bound tight to a wooden cross, bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the crucifixion of Christ; Kong of Kongs!

The sequences taken aboard Captain Englehorn’s embattled old steamer were really filmed on a tramp steamer in San Pedro Harbor.

Rather than display Kong on a theatrical stage as was finally agreed upon, Cooper’s first conception of that unveiling was to present Kong to New York in a huge, outdoor stadium in broad daylight. Choices being considered for the location were Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium. O’Brien went as far as sketching his version of the scene when the director decided in favor of the theatre. Presumably, the Shrine Auditorium was intended to represent New York’s Radio City Music Hall.

hands across the (animator’s) table

O’Brien drew a series of preliminary sketches of the animal at various stages of the film. As in the film, the cities and jungles were fashioned by Mario Larrinaga and Byron L. Crabbe.

All of the animals in the picture were built by the skilled hands of Marcel Delgado, model maker supreme.

Throughout the long history of “Monster” movies, technicians have striven to create new, and blood-curdling sounds to emanate from the vocal cords of their creations. Kong’s fierce, never-to-be-forgotten roar was achieved by the recording, at half speed, of a fully grown lion which was then printed in reverse on the soundtrack.

“King Kong” was completed after one year at a cost of approximately $650,000.00. A full-size bust of Kong was put on display in the forecourt of Sid Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood for the premiere. It was the very same full-scale bust that was used in the production of the movie for some of the closeups of Kong’s face. Of course, the majority of the ape’s appearances on the screen were filmed in Obie’s “Stop Motion” process but there were several times in the run of the film that the full-scale bust was used. The one scene in the film in which a man was dressed in a monkey suit was in the final scene of the movie: Charles Gemora, long associated with playing animals in pictures, donned the gorilla suit for the long shot of Kong climbing up the side of the Empire State Building for his final battle.

music for MAXimum effect

In an adventure film like “King Kong” music plays a vastly important role in creating the proper atmosphere. In many instances film music can make a good film seem better than it actually is. And as for the bad ones, this writer long ago lost count of the miserable pictures that were literally saved by an excellent music score. Similarly, a bad music score can critically wound a decent film. In the case of “Kong”, this was one picture that appeared to have everything going for it. The head of R.K.O.’s music department until 1936 was Max Steiner, a man considered by many film historians to be the most prolific composer of the screen. In his unpublished autobiography, “On The Right Track”, Steiner recalls the growing skepticism on the part of R.K.O.’s executive officers regarding the box office appeal of “Kong.” They had to be repeatedly won over as a collective paranoia recurred over and over again. They thought that the gorilla looked unreal and rather phony, and they were no longer sold on the animated sequences. When it came time for scoring the film they advised Steiner to merely borrow tracks from previous studio films and dub them into the soundtrack of “Kong.” The word was out that no additional money was to be wasted on a film that might turn out to be the ruination of an already dying studio. In other words–no new score and no costly arrangements.

MaxenSteiner’s monster

Fortunately, Cooper re-entered the scene and proved his complete faith in “Kong” once again. “Coop” urged Steiner to write a fresh score for the film and reassured him that he would pay any extra costs from his own pocket. The result was Steiner’s finest hour, the dynamic, heart-pounding score for “King Kong.” The composer set about creating a vast plain of emotional experience set to music. From the moment the film begins with the ominous three bars that fans around the globe universally recognize as Kong’s Theme, to the final, memorable fadeout the listener is caught in a raging onslaught of sound. The slow, gradually building tension of the first hint of arrival on Skull Island is masterfully conveyed as Steiner subtly integrates the deceptive sound of breakers near the shore with the warning drums of unseen natives from somewhere on the beach. As Denham and his crew cautiously leave the shelter of their ship, and enter the apparently empty village they hear a distant chanting somewhere near the great wall up ahead of them.

As they walk steadily nearer the sounds gain strength and momentum until at last the intruders come upon a dazzling ‘sight: the ritualistic sacrifice of a young maiden to something the natives continually call “KONG, KONG.”

However, the momentary safety of the explorers on Skull Island is abruptly interrupted when the tribal chief catches sight of them, and calls a halt to the proceedings. Steiner accents every movement of the chief’s strut as he walks toward the intruders. His slow, deliberate steps are contrasted dramatically by the wild, gyrating advance of the menacing witch doctor. This is only a prelude to the unrestrained frenzy of the natives as they invite KONG to partake of their gift, the now captive Ann Darrow. It is here that Steiner captures the fury, and vengeful fanaticism of the island’s populace in an intoxicated rage. The music begins as the natives are already swept up by the exhilaration of what they plan to do. It throbs, and builds to a fever pitch, exuding an excitement from the screen that cannot fail to touch anyone in the viewing audience, and concludes sharply, abruptly at its very peak leaving the helpless spectator literally gasping for his breath.

Sheet music for piano was published for the score, and Steiner recorded a fifteen-minute suite from the film with the R.K.O. Studio Orchestra.

The Prophet Said (as prophets must)…

The music wonderfully sets the pace at the outset for what is to come, but it is aided almost mystically by the mysterious “Old Arabian Proverb” that precedes the story’s unraveling and stands as a profoundly beautiful warning to all who may fall under the spell of the goddess of love: “And The Prophet Said-And lo, the beast looked upon the face of beauty. And it stayed its hand from killing. And from that day, it was as one dead.” The old Arabian proverb was written for the film by that old Arabian, Merian C. Cooper, as a part of his original treatment for the film in 1930, and has since become a genuine slice of American mythology.

ISSUE AFTER NEXT

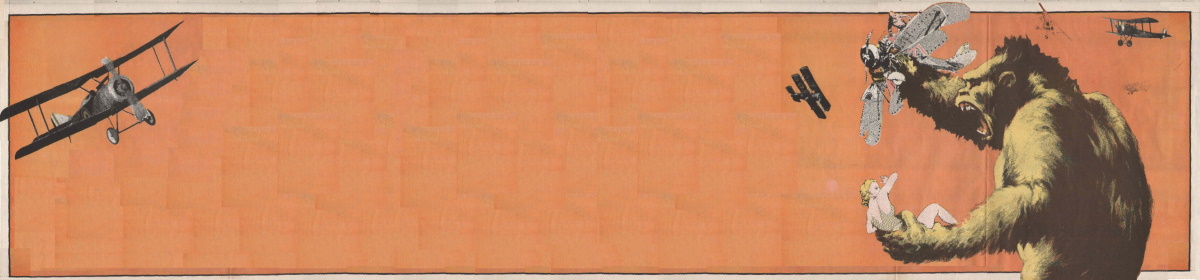

How To Sell A Gorilla!

Part two of Steve Vertlieb’s Chronicles of Kong; some rarely known or remembered Kong curiosities; rare old posters and advertisements, anecdotes about the gala premiere, and other merchandising highlights of the Greatest Campaign on Earth!, portfolios of never-before-seen poster art, and much, much more!