by: ALLAN ASHERMAN

2036 CAME BEFORE 2001

Sometimes it happens that great writers meet great filmmakers and filmmiracles are generated. When Arthur C. Clarke, of SF-fame met the brilliant film producer, Stanley Kubrick, poof! we had 2001-A Space Odyssey. But back in the 1930’s another great author met another great filmmaker in another country, Great Britain, and the result was every bit as revolutionary in its day as 2001 is on ours. Perhaps, more so, for it predicted WWII, bombing of cities from the air, and a halting of progress, with such accuracy that some parts of the film could be used as newsreel footage with no one the wiser. In fact, in one portion of the 1935 film, a mushroom cloud was seen over a caption, which read; 1945!

Even the first flight to the moon was described as being accomplished with multi-stage rockets, as being a mission of observation, of orbiting the moon and of returning to earth without landing.

All these things were in a great film released in 1936!

H.G. Wells’ epic storyline was roughly broken into three phases, all revolving about the city of Everytown, a typical metropolis. The name was chosen to avoid viewer identification with any one area of the world, but Everytown bore a marked resemblance to the London of the time.

In phase one of the story, we see multitudes of bustling, happy people celebrating the coming of Christmas. Spirits are high, but we gradually become very much aware of a feeling of impending doom. This doom, a threatened war, breaks through the happiness in the shape of signs, newspaper headlines and dark skies. We are shown the city and its people, and we then find ourselves in the home of John Cabal, scientist.

It is possible that phases one and two of the film are brought to us as seen through the eyes and mind of John Cabal. This would be particularly logical to assume, for Wells intended “Things to Come” to be a film of human symbols rather than individual characters.

When we first see him, Cabal (Raymond Massey) is entertaining several friends, one of whom, a certain Mr. Passworthy (Edward Chapman), seems strangely unconcerned with the probable holocaust. Young Dr. Harding (Maurice Braddell) is very much concerned. He fears war will bring an end to medical research. Cabal is afraid for the world. “My God,” he shudders, “if war breaks loose again!”

Passworthy, though, regards war as a stimulant to the economy, “War is good for business” sort, and can’t wait.

Deep Wells philosophy

Here we have 3 of the 4 main controlling forces of humanity as Wells saw them:

(1) The Bubble-Headed man who cares about nothing but the joys of the moment. He thinks about the pleasures of life, but is blind to its obligations. He passes over the worthy qualities of mankind, and therefore is given the name “Passworthy.” But he is not really evil, and is alright in his own small way. One might say of him; “He’ll do” or “He’ll pass” – and not much else.

extra ***** 1936: THE END

(2) Youth, caught in the middle of Passworthy and Cabal in the form of Dr. Harding. Youth is in favor of peace, of saving lives, and of questioning.

(3) The stoic, logical man whose long legs are firmly rooted into this world and his faith that people were meant to be the masters of their universe. His quiet moods of rationalization border on the mystical, and he is called “Cabal.” (Which the dictionary defines as a “conspiratorial group,” ironically enough.

WAR!

As Cabal’s little gathering ends, it is learned that Everytown is indeed at war. There is, without warning, an air raid in which unseen multitudes of aeroplanes drop bombs and gas on the city. People are caught in the middle of blasts, without gas masks. Youngsters and the elderly are seen lying in the twisted rubble of department stores and Christmas decorations. Panic reigns among the survivors of explosions. Mobs scurry to places of safety before the next bombs strike. Happy humanity gives way to frightened animal-like groups of charging maniacs of all ages. War has come to Everytown and to the world.

Blitz of ’36!

In the wake of the air raid, mobilization is announced. A grimly determined Cabal and a jubilantly proud Passworthy march off to war, still holding their respective philosophies. The first indication of the “progressiveness of war is seen in the person of little Horrie Passworthy (P. Livingston) Passworthy’s son, lying dead among the rubble of his home, as his father marches off to fight. The terrors of war begin to be realized.

We don’t see the horde of airplanes that bomb Everytown and turn it to the dead, broken pile of buildings we later see in the film. The air raid happens quickly, as quickly as it actually happened a few years later when London was first bombed by the German air force.

The next scene we see is a vast group of airplanes that come through the clouds over a group of cliffs, and fly in formation over another part of Everytown. They are strangely calm, just flying over the city and going on their way after dropping poison gas.

The progress of the war is shown with a montage sequence of tanks; first tanks as they actually appeared in those days, then ultra-modern war-machines capable of crushing whole houses as they roll on.

some uncanny prophecies

As the year 1945 looms before us in the film montage, a soldier’s mutilated corpse, swaying on a barbed wire fence, is suddenly silhouetted by a bright fireball which forms – a mushroom-shaped cloud! Hmm… 1945! Wells even got the year right!

Gradually the world crumbles, desolate, decaying. The weapons become more primitive as factories are destroyed one by one. When nothing new is made the old things are used, until finally the fighters look more like something from the middle-ages. And still they fight. On and on. Civilization is collapsing. Technology is dying. Dead.

The newspapers are shown to become more awkward, until they are only one page of war news scrawled on a blackboard in the town square. From the words on the blackboard it can be seen that people are even beginning to forget how to read.

Still, the war drags on; the years pass ominously before the camera, until 1970. We again find ourselves in Everytown, where we stop our flight through time. We have arrived at a world of despair.

The futility of war is farther shown in a short but highly meaningful scene. Cabal has shot down an enemy pilot (John Clements), who has just dropped poison gas on a city. He is gravely wounded, and Cabal lands to help him. Both men now know how stupid war is. After killing an entire city, the enemy pilot ends by giving his gas mask to a surviving little girl of the town. Just as the thick clouds of poison close over the pilot, he speaks to himself of the irony of it all. Then he shoots himself as the first vapors start burning his lungs. Cabal takes the little girl to safety in his plane.

more uncanny prophecies

Here was another of the film’s ironically real dark prophecies. In World War II (the real one-not the film’s 2nd World War which we have just seen) John Clements joined the Royal Air Force. While flying a mission over France, in 1942, his plane was shot down, and he perished.

Phase two of the story now begins; a phase of ruin, depression of the human spirit, and a total end to progress. Civilization is stuck in the mud. We see the ruined Everytown ruled by Rudolph, an arrogant tribalistic Mussolini-type. We also learn of the “wandering sickness,” future biological warfare’s new equivalent of the black plague. It has stricken half the human race. Sanitary conditions are all gone. There is no defense against this biological onslaught. The victims wander zombie-like across the countryside spreading the plague. Carriers of the disease are shot in the streets. And Rudolph, the “Boss” of Everytown (Ralph Richardson) is still warning! He fights a meaningless, ritualistic war against the “hill people.”

Dr. Harding, who once was youth personified, is old before his time. He has long since run out of medical supplies. He stands helpless and weary before the tattered people of Everytown. When asked what can be done to make a suffering person comfortable, he replies grimly; “Nothing! There is nothing to make anyone comfortable anymore. War is the act of spreading wretchedness and misery!”

an Angel of Science arrives

To this scene of despair descends a streamlined aircraft. The craft and its occupant show no traces of the dusty squalor around them. We learn that the pilot of the plane is John Cabal, grown older but still with a generally youthful appearance. His new home, wherever it may be, has obviously escaped the ruin of war. Through him we learn that there is, after all, some hope for humanity’s recovery and reconstruction.

Cabal mentions that he is a member of an organization called “Wings Over the World.” Comprised of scientists, engineers and foresighted people who are sick of war, and whose aim is to do away with the still-raging scattered conflicts, “Wings Over the World” work to eventually remake the world into a planet ruled by science and reason. We also suspect that Cabal is one of the founders of this movement.

New! Unique! Law AND Sanity!

Cabal confronts the Boss. It is a game of intellectual chess, in which their positions are made known to each other. Cabal informs the Boss that he represents not just law, but “law and sanity.” The Boss needs planes for his fight against the “hill people.” He dickers with Cabal for planes, and when Cabal refuses, he has Cabal imprisoned.

The Boss is Wells’ vision of the fourth controlling type of human being. He is nationalism and tribalism personified. All things that are not flags are cowardly and useless to his sort. He believes just as deeply in primitivism and insanity as Cabal does in progress. He is the opposing force to Cabal, thrusting Passworthy and Harding into the background.

The Boss’s wife, meanwhile, has become intrigued with Cabal. Visiting secretly in his cell, Roxana Black (Margaretta Scott) explains that she has always wanted to escape from this land of squalor. She is a clever, beautiful woman, and she wants Cabal and his land of sanity… sanity which will eventually overpower madness.

The interplay between Cabal and Roxana is so interwoven that we honestly do not know if she is speaking seriously toward him, or he toward her. It may well be that she wanted only to save her Boss, and he wanted only to escape. But it is also possible that they saw, in each other, reflected images of human hope.

WINGS to COME!

We now see the futuristic headquarters of Wings Over the World, in Basra. The men, concerned about the safety of their friend, are told of his whereabouts by Gordon, a young pilot (Derrick De Marney), who managed, with the aid of Harding and Cabal, to escape from Everytown in a rickety airplane. The scientists, being men of responsible action, as well as knowledge, jump to the challenge.

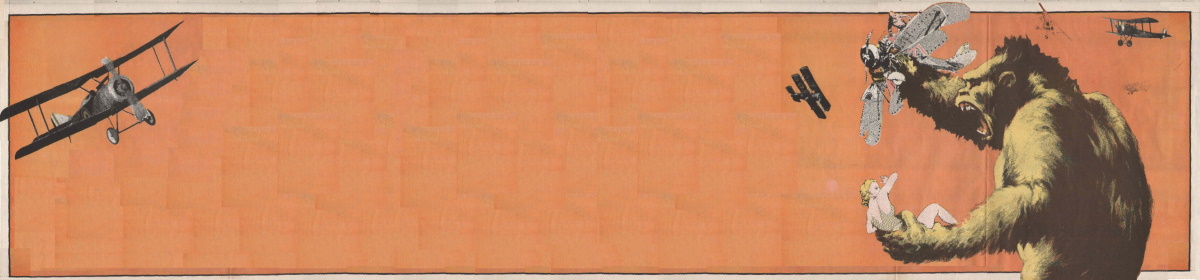

Immediately the huge airfleet of “Wings Over the World” is readied. They fly over Everytown, drop cylinders of their new “gas of peace,” a harmless sleep gas, and free Cabal. The armada of ultra-stylized gigantic airships speckles the sky like a flock of droning dragonflies.

The fleet swoops over Everytown. The Boss, desperate to salvage his position of power, commands the air-force he has scrounged from ruined airplanes to fight the giant, batlike airships of the invaders.

It is an almost comic sight… fragile, ridiculously obsolete, outnumbered airplanes trying to out-maneuver sophisticated, sleek mechanical wonders! One by one the dinky relics are downed like antiques bumped off a shelf. Wings Over the World claims easy air victory… now for the land…

Bomb for Peace – it works!

The Peace Gas is dropped, and Cabal is rescued. All the people of Everytown revive, except Rudolph, the Boss. His mind has fought so hard against the Peace Gas and the changes to come that he has died. Cabal, standing over him, observes that he is:

“Dead, and his world dead with him. But we will build a new world. The new world with the old stuff. Our job is only beginning.”

Maybe Cabal’s job was only beginning, but producer Alexander Korda’s task just was becoming more difficult. The sections of the film dealing with the present of the time were over. From here on, everything had to be of an atypical appearance. Now the designs and the concepts of all the people connected with the film’s production would be taxed to the limit.

building Tomorrow – Yesterday

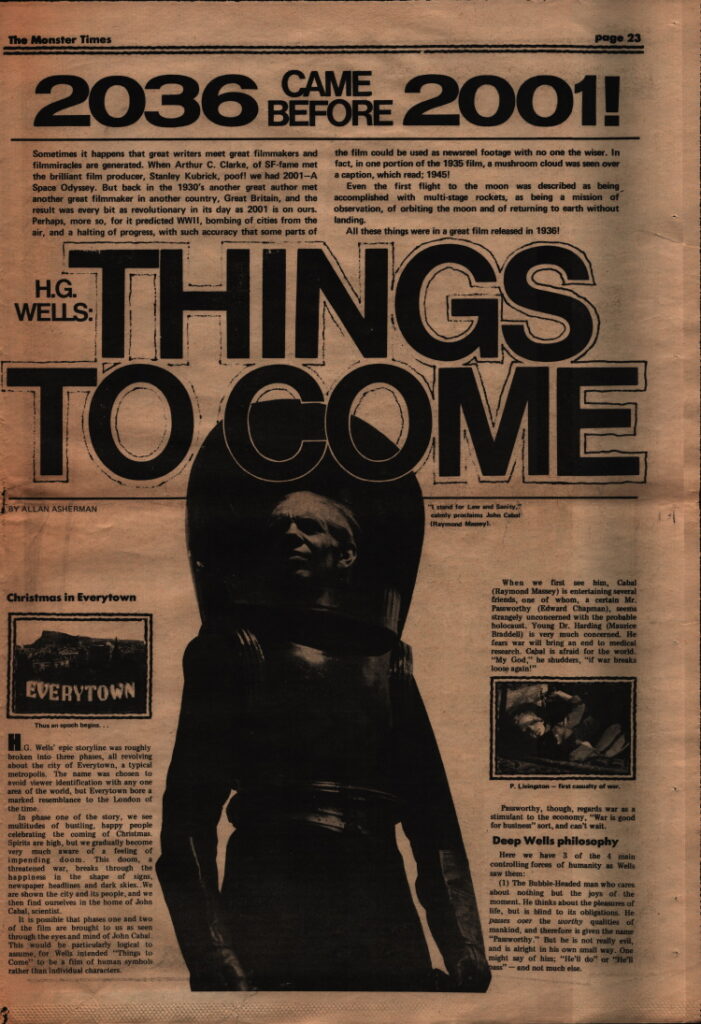

Even the preceding scenes featuring the ruined Everytown were extremely difficult. An entire city had to be built, as it would be impossible to use existing buildings. The city had to be destroyed after the bombing sequences, to be shown in ruins for the remaining second third of the film. How could it be done within the film’s budget?

William Menzies had gotten the “feel” of the story while aiding Wells in completing his screenplay. Now, together with Vincent Korda, Menzies preceeded to design the production’s appearance. His massive style, roughly the same form that was seen throughout “Gone With the Wind.” (Menzies later also worked on a version of “Thief of Bagdad” for Korda), blended in smoothly with the moral symbolism of Well’s storyline.

Alexander Korda was now faced with the problem of accepting the uniformly immense production style of Menzies together with his brother, Vincent’s, designs for the specific settings, which were spell-binding.

Wells, who had participated in their design, had seen to it that the architectural styles used in the film were merely symbols of their eras and the philosophies of their times. He liked the preliminary sketches. But how could they be built without using the money set aside for the futuristic city yet to be built? Or how could the future sets be built without having to eliminate the settings of the initial city? In this all-important area, an ingenious compromise was reached.

It was agreed that, in order for the sets and buildings required by the storyline to be photographed, they must first be built in miniature. But the proportion of their construction was another matter. Actors could not be shown together with the city by this method to the extent needed. Still, Wells regarded the scenes of thousands of people running through the past and future cities “highly necessary” to the spirit of the story.

The solution? Lower stories of most buildings were to be built fullscale on the Elstree backlots. Upper parts of the buildings would be built in miniature within the sound stages. The lower and upper stories of structures would be integrated onto one piece of film by means of associated photographic techniques such as split-screen, matting, mirror-shots and rear-projection. For this work, two rare talents were imported to London Films.

Ned Mann had built miniatures for Paramount and RKO films, including “Deluge” (in which New York City was drowned under a tidal wave), and “Dirigible” (A Cecil B. DeMille film). He was an expert in his craft, and always worked in the largest scale possible, so as to add detail to his models. He worked with Menzies to paint huge realistic backdrops of buildings for indoor and outdoor use. Because of these “drops”, some buildings did not have to be built at all. The structures in front of the camera were erected, but the buildings off to the side streets and in the back of other houses, could be painted on canvas and hung in the streets. Because of skillful painting, they photographed like actually constructed buildings. The superimposed miniatures completed the illusion of the vast cities.

Harry Zech, an American special-effects technician who did pioneer work in perfecting split-screen photography, also became part of the staff of “Things to Come.” He had started working in films with Mack Sennett, and so had many years to perfect his techniques. He had also worked with other special-effects technicians and, like Mann, had the ability to devise completely new effects at a moment’s notice.

For the more intricate scenes involving live actors combined photographically with miniatures, rear-projection screens were set up in the miniature scale buildings, and on these screens was projected footage of the actors scattered around the full-scale lower stories. When seen on film, combined with other angles involving split-screen, it looks like multitudes of people are running through full-size, complete buildings.

Reconstruction by Technocracy

The present was finished, now, in the film. With the guidance of Cabal’s organization, reconstruction began. Old buildings were razed, huge excavations were dug. Unheard-of machines molded super-size panels from plastics stronger than steel, and other machines erected the panels and shaped balconies, symmetrical buildings.

The new city is huge and clear, completely devoid of dirt. With its own artificial sunlight, built beneath ground level but still not completely cut-off from the world above, it is a completely controlled environment. Spiraled roads stretch from the depths of the city to the surface, and multi-laned highways traverse the megopolis. The new world is here!

EVERYTOWN: 2036!

One of directorial wizard William Menzies’ favorite photographic technique was used to provide us with our first glimpse of the completed, futuristic Everytown.

First, an extremely long shot of the sky. The camera slowly dollies down to the cliffs surrounding the city, then the caption “2036” explodes upon the screen! The camera zooms upward and out until the entire underground excavation is visible. Slowly focusing in toward the city, the camera reveals the tops of the futuristic buildings, then the entire structures. With a slow dissolving shot melting our vision, changing angles to down shots of the majestic buildings, with hordes of people streaming in and out of palaces, monorails speeding back and forth, countless varieties of cars and elevators all moving and working. The city is alive! A giant complex of machine and man!

This shot was accomplished by first photographing a miniature of the cliffs and surrounding land, then zooming in for a closeup of the miniature excavation. At this point there was a brief shot of the city, with miniature people running from place to place on conveyor belts. Then, while the attention of the audience is fixed on the city, there is a dissolve to the miniature city, from a lower level. Process screens were positioned within the buildings, and people were double-exposed in the buildings. At the same time, Mann’s miniature vehicles were in action. The result: a panned shot of an apparently full-sized city, with multitudes of people and machines moving around. A beautiful illusion!

Wells’ Brave New-topia

With the new world come new people. It is now 2036. John Cabal is gone, but in his place is his great-grandson, Oswald Cabal, again Raymond Massey, the World President. Everytown is now the world capital.

The society is divided into two groups; scientists and artists. Science forges onward, uncovering one secret of nature after another. The thinkers are happy with their ever-accelerating progress, but the artists are not.

beware of meeks gearing rifts

Spokesman of the artists is Theotocopulos (Sir Cedric Hardwicke). Speaking on a worldwide television broadcast, he asks the people for a reason to justify this constant discovery. Things used to be so simple in the “old days,” he says. In those days” the artists were the creators of the world. They were respected and important. There were good times, and everyone was securely happy. Now, he says, science is making discoveries so profound that they are dwarfing the work of artists. Theotocopulos and all the people like him are frightened.

We all remember how good things were back there in good old 1971, don’t we?

The focal point of their fears is the huge space gun, which has been built to rocket two people into orbit around the moon. This is terrible, reason the artists, who would rather paint a place from imagination than by visiting it-which might take courage.

Appealing for support, Theotocopulos begs the populace of Everytown to join him in putting an end to the forces of science by smashing the space gun. Pointing to a huge photograph of Cabal, Theotocopulos tells his followers:

“There… There is the man who would offer up his daughter to the devils of science!” But the coup fails, and the launching goes on as scheduled.

It might be worth noting that Theotocopulos used a 100-foot high television screen to project his image as he bad-mouthed science.

Raymond Passworthy again, Edward Chapman, a descendant of the Passworthy of John Cabal’s day, asks Oswald Cabal for his views as the space bullet rockets toward the moon. Aboard the craft are Cabal’s daughter and Passworthy’s son. Theotocopulos and his followers have been frustrated in their attempt to destroy the invention and have returned to their homes, wondering what new miracles are to come.

Cabal explains his philosophy of life and of man in a speech worthy of Shakespeare in its artistry and meaning.

We recreate that final stunning dialogue on the page at right in a special MT film-comics treatment…

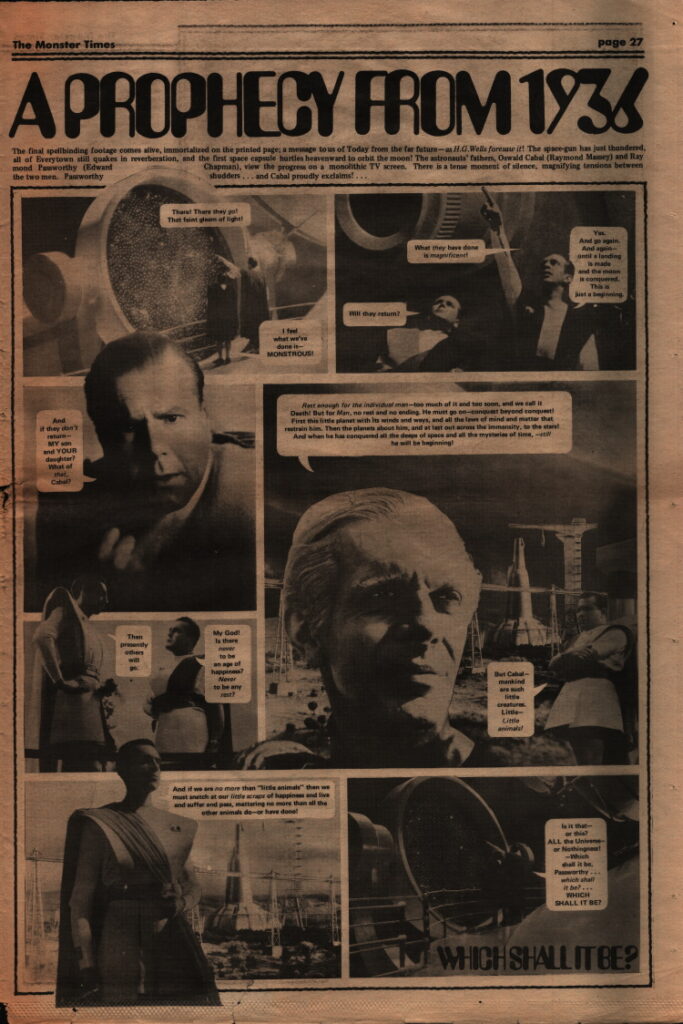

A PROPHECY FROM 1936

The final spellbinding footage comes alive, immortalized on the printed page; a message to us from Today from the far future – as H.G. Wells foresaw it! The space-gun that just thundered, all of Everytown still quakes in reverberation, and the first space capsule hurtles heavenward to orbit the moon! The astronauts’ fathers, Oswald Cabal (Raymond Massey) and Raymond Passworthy (Edward Chapman), view the progress on a monolithic TV screen. There is a tense moment of silence, magnifying tensions between the two men. Passworthy shudders… and Cabal proudly exclaims!…

Cabal: There! There they go! That faint gleam of light!

Passworthy: I feel what we’ve done is – MONSTROUS!

Cabal: What they have done is magnificent!

Passworthy: Will they return?

Cabal: Yes. And go again. And again – until a landing is made and the moon is conquered. This is just a beginning.

Passworthy: And if they don’t return – MY son and YOUR daughter? What of that, Cabal?

Cabal: Rest enough for the individual man – too much of it and too soon, and we call it Death! But for Man, no rest and no ending. He must go on – conquest beyond conquest! First this little planet with its winds and ways, and all of the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him. and at last out across the immensity, to the stars! And when he has conquered all the deeps of space and all the mysteries of time, -still he will be beginning!

Passworthy: But Cabal – mankind are such little creatures. Little – Little animals!

Cabal: And if we are no more than “little animals” then we must snatch at our little scraps of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than all the other animals do – or have done!

Cabal: Is it that – or this? ALL the Universe – or Nothingness! – Which shall it be, Passworthy… which shall it be?… WHICH SHALL IT BE?

WHICH SHALL IT BE?

Production and Musical Notes

Which SHALL it be?

Thus ends “Things to Come,” first with Raymond Massey’s voice echoing, “Which shall it be” until the question is chimed by a huge chorus, accompanied by a full orchestra, the challenging words, “Which shall it be?” climaxing on a crescendo as the scene blacks out. We, the audience are left now to ponder the future of mankind… to a musical score created by Arthur Bliss, who, after writing music for “Things,” was to be knighted and made official composer to the Queen of England.

Bliss’ score for “Things to Come” was considered so special that it became the first motion-picture soundtrack ever to be recorded on discs for commercial sale. A set of 78 RPM records was issued in 1936, and in the early 1950’s, RCA Victor again recorded the score, this time with Bliss conducting the score in stereophonic sound. This recording has been reissued in England.

For the “2036” sequence of the film, certain settings had to be built entirely in the miniature scale. These included the space gun, the factory used in the reconstruction montage, the huge construction machines that rebuilt “Everytown,” and the future city itself (for its first appearance in an extreme long shot).

With proper editing and the addition of appropriate sound effects, streams of puppets were made to look like crowds of people. To this day, certain scenes in “Things to Come” mystify audiences in this manner. It is impossible to tell what portions of the sets were miniatures, and what portions were built full scale.

1936 to 2036 – Women’s Lib to come!

One scene that was cut from the film, yet appears in the printed version of the script is a dialogue between Oswald Cabal and his wife Rowena (Raymond Massey and Margaretta Scott, carrying their roles into the future). Rowena was a descendant of Roxana Black, wife of the Boss. In the dialogue, Cabal stated his views on the “women of the world who live for the purpose of proving that they are better than men,” rather than “working with them to improve the world.” Also during the scene we learn that Cabal has been divorced from his wife, that she is violently against their daughter being sent to the moon. Those who think women’s lib is a passing fad or a throwback to the suffragettes find little solace in such a vision.

Raymond Massey, then relatively unknown, was chosen for the dual role of John and Oswald Cabal. His acting style at the time was such that he could perform with an easy, flowing quality. He also had the ability to tighten up his relaxed style during moments of crisis in the lives of both Cabals. In Massey, Korda found an actor who could be a relatively quiet, philosophical sort with a powerful sense of human hope and cosmic confidence. It was a type of acting that projected a powerful aura of wisdom and leadership.

Just as Korda’s films had made stars of others including Charles Laughton, “Things to Come” was to start Massey down the starring role of films. Later, in 1940, Massey achieved the ultimate in character identification when he portrayed Abraham Lincoln with the same qualities of dynamic life that he instilled in John and Oswald Cabal.

The role of Rudolph, “Boss” of Everytown, went to Ralph Richardson. In his capable hands, the Boss became a character who, it was plain, believed he was the most important person in the world, and that he was therefore supposed to take over everything in it. Primitivism and tribalism personified, befit Mussolini and Hitler to a “T.”

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, one of the greatest portrayers of villainy, was Theotocopulos. He was the anarchist of yesterday combined with the reactionary of today. His manner balanced the scale of dramatic moments when it clashed with Massey’s role.

The role of Theotocopulos was originally supposed to have been played by Ernest Thesiger. In Korda’s group of fantasy films, Thesiger is remembered for his role of “Dr. Maydig,” in “The Man Who Could Work Miracles.” He is most famous, however, for his role of Dr. Pretorius in “The Bride of Frankenstein.”

advice to us from a past Future

In 1936, Herbert George Wells, Alexander and Vincent Korda, William Cameron Menzies and a staff of additional geniuses teamed together to make a motion-picture: “Things to Come.” A large part of “Things to Come” has already come to pass. The question of “Which shall it be?” as yet to be answered as there are still many Passworthy’s about who would like to put an end to the space program in favor of war. Which shall it be? No matter what the answer, the question of today into a wondrous tomorrow will hopefully always be remembered as having been asked first if not best in a film produced in the past; in 1936, in England. “Things to Come.”

Which SHALL it be?