by JOE KANE

If you liked the way the world ended and ended and ended issue before last, you’ll love the way it ends and ends and ends yet ever again, this one, as Joe Kane gleefully examines the freaks and misshapen human-critters who resulted from man’s toying with elements beyond his control, elements Like U-235, nuclear warheads, and alcoholic Hollywood screenwriters.

SEE! Joe Kane chuckle as he tears apart rotten movie scripts!

SEE! Joe Kane laugh uproariously as he tramples dumb Hollywood monster-movie-making cliches!

SEE! Joe Kane cackle with glee as he describes human mutations who resembled walking-dead pizza-pies!

SEE! Joe Kane himself in our special MT photo-comix (page 9) try to do better in a low-budget cheapie mini-movie produced and directed by the great team of Brill & Waldstein!

The subject, I believe, was the end of the world. A pleasant enough topic, that, and an event that, if Hollywood had its way, would have happened years ago. In fact, it did happen … and not once, but many times. But never fear, the set directors have always managed to scotch tape Earth together again in time for the next film and that old stock footage of the atomic explosion. It’s even worse in Tokyo, that miniature city that had been blown up, destroyed, disintegrated, and scattered to the atomic winds in film after film. You wouldn’t want to open an insurance office there.

some mushrooms, most toadstools

Last time out I discussed a few examples of the various ways filmmakers dealt with the new and terrifying presence of nuclear energy. While most of the films dealing with the destructive aspects of nuclear energy could, by their very subject chilling matter, be classed as horror films, a few overlapped into other genres.

THE ATOMIC KID, a 1954 fiasco about a pair of (oy!) bumbling uranium-hunters (played by Mickey Rooney and Robert Strauss), was a so-called “comedy” that had Rooney transform from a jittery loser into a Las Vegas gambling shark through the effects of radioactivity – I don’t remember the exact details, let it suffice to say that that’s what happens in the film. If you’ve been fortunate enough to miss this flick so far, your luck (if you’re an inveterate TV-watcher) might very well run out, since THE ATOMIC KID is a television staple, frequently dug out of Metromedia’s scaly stockpile on Saturday afternoons. Be forewarned!

Other nuclear films that crossed over from the strict horror genre include Peter Watkins’ frightening simulated documentary, THE WAR GAME, a harrowing look at chaotic conditions in Britain after the hard rain has finally fallen; SPLIT-SECOND, a hydrogen-hyped 1953 remake of the PETRIFIED FOREST, with gangsters and hostages frantically fleeing through the desert when they discover that their hide-out is situated smack in the center of a nuclear testing ground!; the paranoid FAIL-SAFE and SEVEN DAYS IN MAY; and the satirical DR. STRANGELOVE, OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB.

References to the Bomb are heard in a great number of other post-war films in which it is not dealt with directly but felt instead as an ominous presence, as it was throughout the 50’s in both reel and real life.

Issue before last we took a brief look at Arch Oboler’s Five. If Five represented the first honest screen attempt to successfully exploit a vision of self-induced global massacre, DR. STRANGELOVE carried the machinations behind that drastic move of worldwide suicide to their logical, and therefore most absurd, extensions. More than any other single work in this genre, Kubrick’s film exposes the kind of competitive paranoia that accompanied the potentially deadly discovery of the Bomb and the self-destructive appetites it whets. The world of the deranged Dr. Strangelove is inhabited by powerful paranoids (Gen. Jack D. Ripper), pompous patriots (Gen. Buck Turgidson), inept aimless administrators (Pres. Merkin Muffley), hawks hellbent on war at any cost (Maj. Bat Guano), and high-level lunatics of all stripes, and it was Kubrick’s special skills that made this film both funny and unsettling at the same time. DR. STRANGELOVE emerged (so far, at least) as the ultimate statement on the Bomb and its destructive effects on the mind and body of Man. Within several months of Strangelove’s release, two other major studio productions, FAILSAFE (dealing with the possibility and penalties of accidental nuclear attack) and SEVEN DAYS IN MAY (about an attempted military coup in Washington) hit the screen, but after that the status of the atomic bomb as 20th Century ogre began to diminish as the threat of world obliteration gradually became accepted as just another part of life. Nuclear films of the 50’s and early 60’s not only fed the hysteria of a frightened movie-going public, but eventually starved it out as well through formula repetition. When you keep getting the same stale, ghastly, unsatisfactory answer, you tend to lose interest in the question.

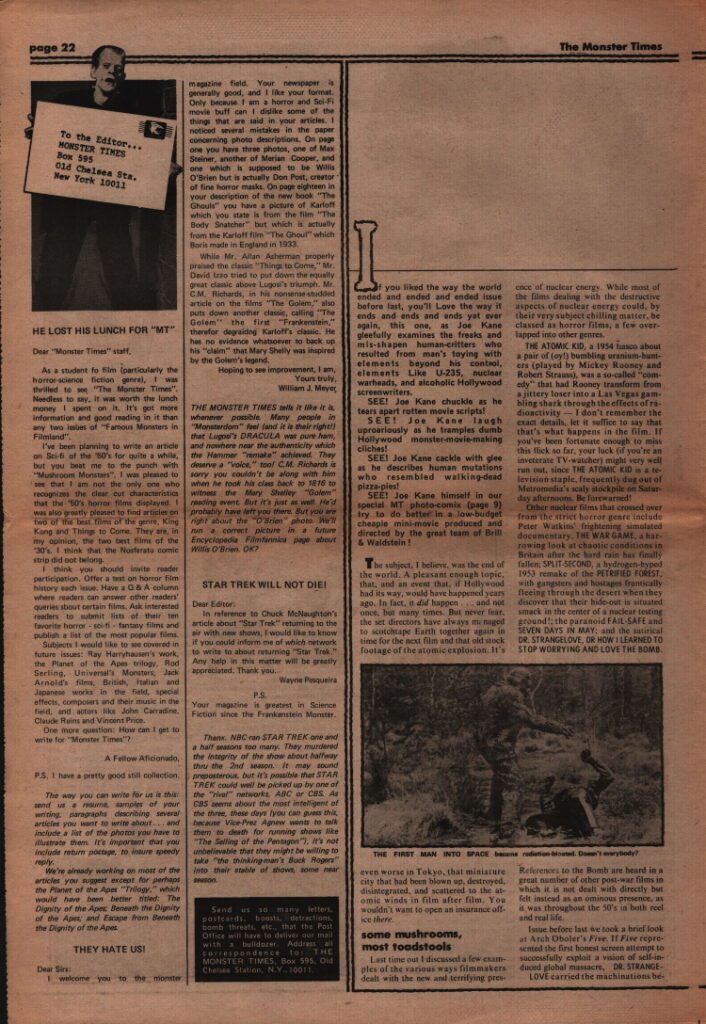

the monster that turned into Brooklyn

One of my favorite harmless past times is making up categories to put things in, a hobby that isn’t unique unto me. Having established that, I’d like to talk a little bit about the most frequently re-occurring theme in nuclear films, the Human-Mutation theme. Last time I cited briefly AIP’s THE AMAZING COLOSSAL MAN as an example of this type of film. Like that one, most of the Human-Mutation films were concerned with computing the possible effects that wayward radioactivity might have on an isolated man. Stretching the imagination half-heartedly in certain limited and all too often patently predictable directions, and spawning after each successful film a litter of imitations, THE TYPICAL HUMAN-MUTATION FILM.

Oh boy! We soon saw features of atomic pioneers (THE CREEPING UNKNOWN) or escaped convicts (THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN ALIVE – director Allen Dwan’s unfortunate screen farewell) or some other wandering worthy who accidentally absorbs radioactive particles and subsequently grows tall (THE AMAZING COLOSSAL MAN) or small (THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN) or zombielike (CREATURE WITH THE ATOM BRAIN) or scaly (FIRST MAN INTO SPACE) or metallic (THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN ALIVE) or bloated & disfigured (HAND OF DEATH) or beast-like and unruly (BEAST OF YUCCA FLATS). All these heroes share two things in common – all are stripped of their original identities and all exhibit a marked tendency towards freaking out after the transformation.

Following the usual ironic and ambiguous (to allow for a possible sequel) destruction of the civilization-stripped mutant, the formula film usually coughs to an end with a ‘heavy’ message along the order of: When will “We” or “Mankind” or “Russia” learn to stop messing with the forces of “Nature” or “God” or the “United States?” – the culprits subject to change according to the “philosophical” bent of the filmmaker. The answer to this thought-provoking query is a rueful shake of some survivor’s head, a final, distanced shot of the fallen monster – a victim of forces beyond his control and understanding – not to mention God and Nature’s and America’s and Russia’s! And we see a slowing title … a ponderous THE END??? across the darkening screen. It looks like a winner, C.B.!

quaint, quaking equation:

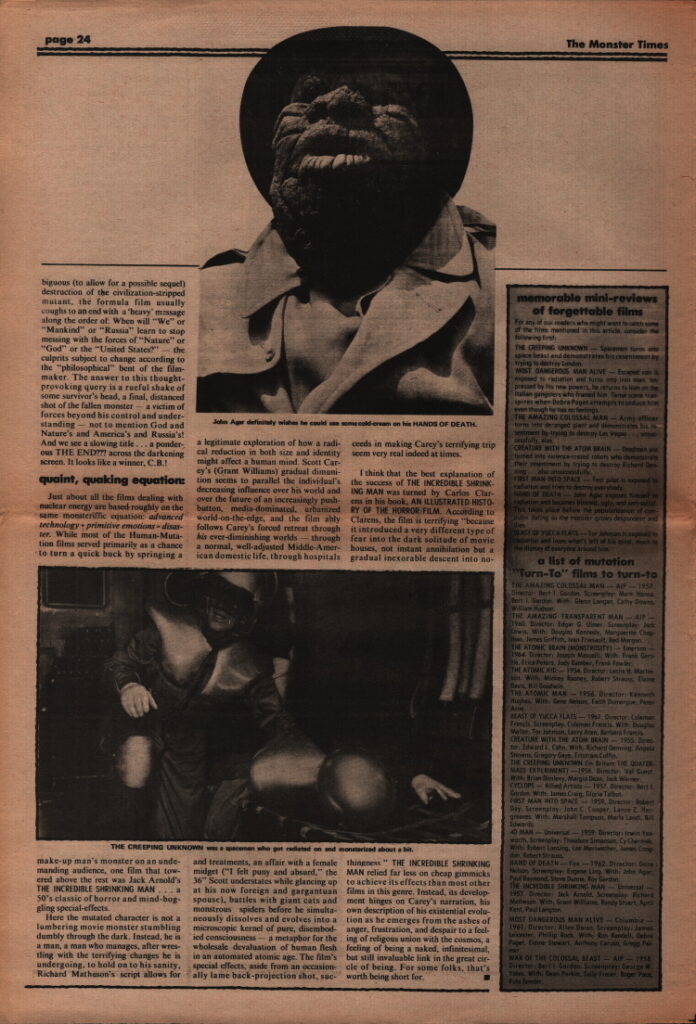

Just about all the films dealing with nuclear energy are based roughly on the same monsterisfic equation: advanced technology + primitive emotions = disaster. While most of the Human-Mutation films served primarily as a chance to turn a quick buck by springing a make-up man’s monster on an undemanding audience, one film that towered above the rest was Jack Arnold’s THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN …a 50’s classic of horror and mind-boggling special effects.

Here the mutated character is not a lumbering movie monster stumbling dumbly through the dark. Instead, he is a man, a man who manages, after wrestling with the terrifying changes he is undergoing, to hold on to his sanity, Richard Matheson’s script allows for a legitimate exploration of how a radical reduction in both size and identity might affect a human mind. Scott Carey’s (Grant Williams) gradual diminution seems to parallel the individual’s decreasing influence over his world and over the future of an increasingly pushbutton, media-dominated, urbanized world-on-the-edge, and the film ably follows Carey’s forced retreat through his ever-diminishing worlds — through a normal, well-adjusted Middle-American domestic life, through hospitals and treatments, an affair with a female midget (“I felt puny and absurd,” the 36″ Scott understates while glancing up at his now foreign and gargantuan spouse), battles with giant cats and monstrous spiders before he simultaneously dissolves and evolves into a microscopic kernel of pure, disembodied consciousness – a metaphor for the wholesale devaluation of human flesh in an automated atomic age. The film’s special effects, aside from an occasionally lame back-projection shot, succeeds in making Carey’s terrifying trip seem very real indeed at times.

I think that the best explanation of the success of THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN was turned by Carlos Clarens in his book, AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THE HORROR FILM. According to Clarens, the film is terrifying “because it introduced a very different type of fear into the dark solitude of movie houses, not instant annihilation but a gradual inexorable descent into nothingness.” THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN relied far less on cheap gimmicks to achieve its effects than most other films in this genre. Instead, its development hinges on Carey’s narration, his own description of his existential evolution as he emerges from the ashes of anger, frustration, and despair to a feeling of religious union with the cosmos, a feeling of being a naked, infinitesimal, but still invaluable link in the great circle of being. For some folks, that’s worth being short for.