a review By: DEAN ALPHEOUS LATIMER

Bike Rogers – merchandisaster

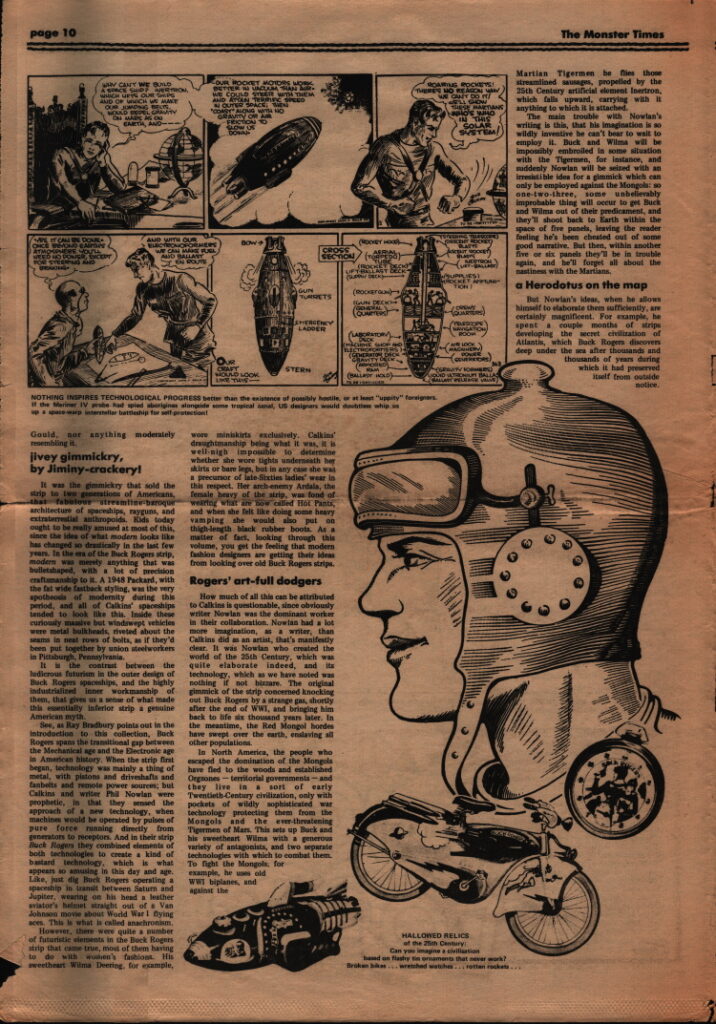

You don’t see Buck Rogers stuff around much anymore, which is probably just as well. When I was a little kid, I mean real little, about four or five, my older brother talked my folks into buying him a Buck Rogers bicycle. They were going to get him a bicycle anyway, so he insisted it be a Buck Rogers bike, and against their better judgment they got it for him. Now, there were flaws in this item which should be obvious from one look at the picture. It looks properly imposing, sure, with the streamlined tin fuselage – real tin, too, aluminum being still in the developmental stage at the time – and the funny horn, and the snazzy handgrips, and the clicky little Saturn on the starboard side … But the problem of course was that every time the chain slipped off the sprocket, or one of the tires blew, or a spoke sprung loose, you had to remove the whole bloody fuselage to get to the infected area. And this could only be done by getting up under the thing with a wrench, and you invariably sliced up your fingers on the sharp tin edge doing this, and the edge was always rusty and full of tetanus, and the tin would warp up out of shape so you’d have to bang it back flat with a hammer … The Buck Rogers bike was a tragically defective item.

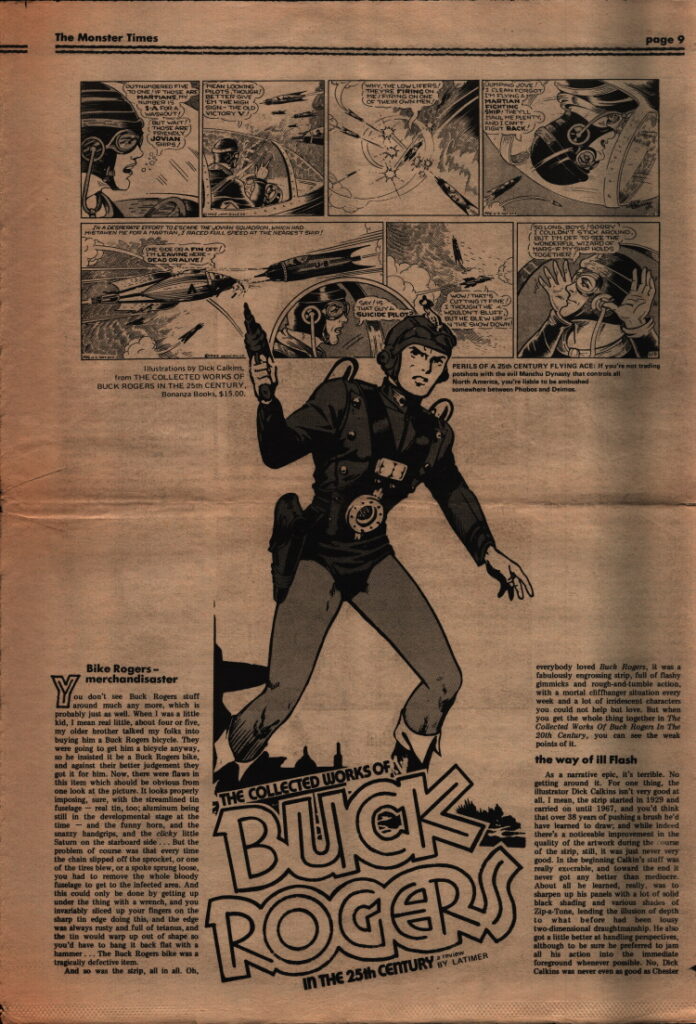

And so was the strip, all in all. Oh, everybody loved Buck Rogers, it was a fabulously engrossing strip, full of flashy gimmicks and rough-and-tumble action, with a mortal cliffhanger situation every week and a lot of iridescent characters you could not help but love. But when you get the whole thing together in The Collected Works Of Buck Rogers In The 20th Century, you can see the weak points of it.

the way of ill Flash

As a narrative epic, it’s terrible. No getting around it. For one thing, the illustrator Dick Calkins isn’t very good at all. I mean, the strip started in 1929 and carried on until 1967, and you’d think that over 38 years of pushing a brush he’d have learned to draw; and while indeed there’s a noticeable improvement in the quality of the artwork during the course of the strip, still, it was just never very good. In the beginning Calkin’s stuff was really execrable, and toward the end it never got any better than mediocre. About all he learned, really, was to sharpen up his panels with a lot of solid black shading and various shades of Zip-a-Tone, lending the illusion of depth to what before had been lousy two-dimensional draughtsmanship. He also got a little better at handling perspectives, although to be sure he preferred to jam all his action into the immediate foreground whenever possible. No, Dick Calkins was never even as good as Chester Gould, nor anything moderately resembling it.

jivey gimmickry, by Jiminy-crackery!

It was the gimmickry that sold the strip to two generations of Americans, that fabulous streamline-baroque architecture of spaceships, rayguns, and extraterrestrial anthropoids. Kids today ought to be really amused at most of this, since the idea of what modern looks like has changed so drastically in the last few years. In the era of the Buck Rogers strip, modern was merely anything that was bullet-shaped, with a lot of precision craftsmanship to it. A 1948 Packard, with the fat wide fastback styling, was the very apotheosis of modernity during this period, and all of Calkins’ spaceships tended to look like this. Inside these curiously massive but windswept vehicles were metal bulkheads, riveted about the seams in neat rows of bolts, as if they’d been put together by union steelworkers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

It is the contrast between the ludicrous futurism in the outer design of Buck Rogers spaceships, and the highly industrialized inner workmanship of them, that gives us a sense of what made this essentially inferior strip a genuine American myth.

See, as Ray Bradbury points out in the introduction to this collection, Buck Rogers spans the transitional gap between the Mechanical age and the Electronic age in American history. When the strip first began, technology was mainly a thing of metal, with pistons and driveshafts and fanbelts and remote power sources; but Calkins and writer Phil Nowlan were prophetic, in that they sensed the approach of a new technology, when machines would be operated by pulses of pure force running directly from generators to receptors. And in their strip Buck Rogers they combined elements of both technologies to create a kind of bastard technology, which is what appears so amusing in this day and age. Like, just dig Buck Rogers operating a spaceship in transit between Saturn and Jupiter, wearing on his head a leather aviator’s helmet straight out of a Van Johnson movie about World War I flying aces. This is what is called anachronism.

However, there were quite a number of futuristic elements in the Buck Rogers strip that came true, most of them having to do with women’s fashions. His sweetheart Wilma Deering, for example, wore miniskirts exclusively. Calkins’ draughtsmanship being what it was, it is well-nigh impossible to determine whether she wore tights underneath her skirts or bare legs, but in any case she was a precursor of late-Sixties ladies’ wear in this respect. Her arch-enemy Ardala, the female-heavy of the strip, was fond of wearing what are now called Hot Pants, and when she felt like doing some heavy vamping she would also put on thigh-length black rubber boots. As a matter of fact, looking through this volume, you get the feeling that modern fashion designers are getting their ideas from looking over old Buck Rogers strips.

Rogers’ art-full dodgers

How much of all this can be attributed to Calkins is questionable, since obviously writer Nowlan was the dominant worker in their collaboration. Nowlan had a lot more imagination, as a writer, than Calkins did as an artist, that’s manifestly clear. It was Nowlan who created the world of the 25th Century, which was quite elaborate indeed, and its technology, which as we have noted was nothing if not bizarre. The original gimmick of the strip concerned knocking out Buck Rogers by a strange gas, shortly after the end of WWI, and bringing him back to life six thousand years later. In the meantime, the Red Mongol hordes have swept over the earth, enslaving all other populations.

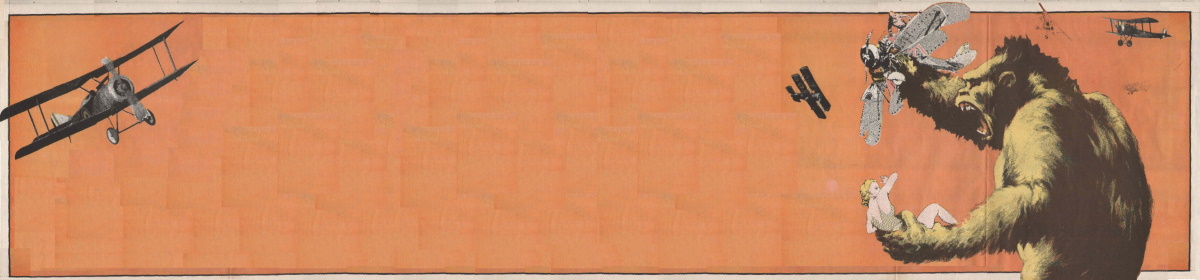

In North America, the people who escaped the domination of the Mongols have fled to the woods and established Orgzones – territorial governments – and they live in a sort of early Twentieth-Century civilization, only with pockets of wildly sophisticated war technology protecting them from the Mongols and the ever-threatening Tigermen of Mars. This sets up Buck and his sweetheart Wilma with a generous variety of antagonists, and two separate technologies with which to combat them. To fight the Mongols, for example, he uses old WWI biplanes, and against the Martian Tigermen he flies those streamlined sausages, propelled by the 25th Century artificial element Inertron, which falls upward, carrying with it anything to which it is attached.

The main trouble with Nowlan’s writing is this, that his imagination is so wildly inventive he can’t bear to wait to employ it. Buck and Wilma will be impossibly embroiled in some situation with the Tigermen, for instance, and suddenly Nowlan will be seized with an irresistible idea for a gimmick which can only be employed against the Mongols: so one-two-three, some unbelievably improbable thing will occur to get Buck and Wilma out of their predicament, and they’ll shoot back to Earth within the space of five panels, leaving the reader feeling he’s been cheated out of some good narrative. But then, within another five or six panels they’ll be in trouble again, and he’ll forget all about the nastiness with the Martians.

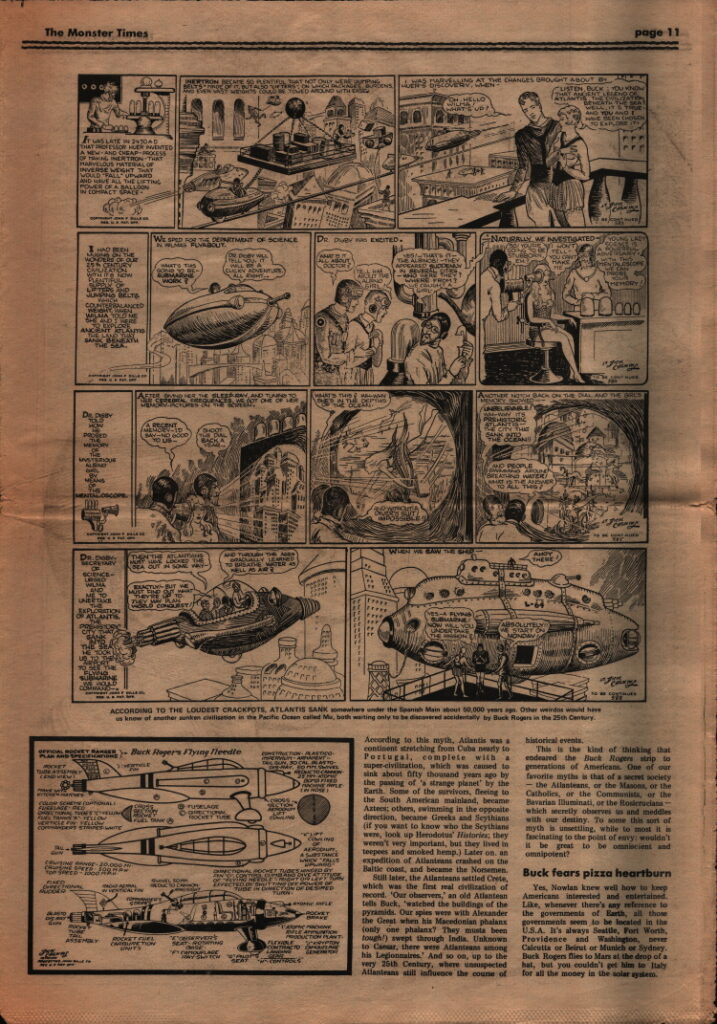

a Herodotus on the map

But Nowlan’s ideas, when he allows himself to elaborate them sufficiently, are certainly magnificent. For example, he spent a couple months of strips developing the secret civilization of Atlantis, which Buck Rogers discovers deep under the sea after thousands and thousands of years during which it had preserved itself from outside notice.

According to this myth, Atlantis was a continent stretching from Cuba nearly to Portugal, complete with a super-civilization, which was caused to sink about fifty thousand years ago by the passing of ‘a strange planet’ by the Earth. Some of the survivors, fleeing to the South American mainland, became Aztecs; others, swimming in the opposite direction, became Greeks and Scythians (if you want to know who the Scythians were, look up Herodotus’ Histories; they weren’t very important, but they lived in teepees and smoked hemp.) Later on, an expedition of Atlanteans crashed on the Baltic coast, and became the Norsemen.

Still later, the Atlanteans settled Crete, which was the first real civilization of record. ‘Our observers,’ an old Atlantean tells Buck, ‘watched the buildings of the pyramids. Our spies were with Alexander the Great when his Macedonian phalanx (only one phalanx? They musta been tough!) swept through India. Unknown to Caesar, there were Atlanteans among his Legionnaires.’ And so on, up to the very 25th Century, where unsuspected Atlanteans still influence the course of historical events.

This is the kind of thinking that endeared the Buck Rogers strip to generations of Americans. One of our favorite myths is that of a secret Society – the Atlanteans, or the Masons, or the Catholics, or the Communists, or the Bavarian Illuminati, or the Rosicrucians – which secretly observes us and meddles with our destiny. To some this sort of myth is unsettling, while to most it is fascinating to the point of envy: wouldn’t it be great to be omniscient and omnipotent?

Buck fears pizza heartburn

Yes, Nowlan knew well how to keep Americans interested and entertained. Like, whenever there’s any reference to the governments of Earth, all those governments seem to be located in the U.S.A. It’s always Seattle, Fort Worth, Providence and Washington, never Calcutta or Beirut or Munich or Sydney. Buck Rogers flies to Mars at the drop of a hat, but you couldn’t get him to Italy for all the money in the solar system.