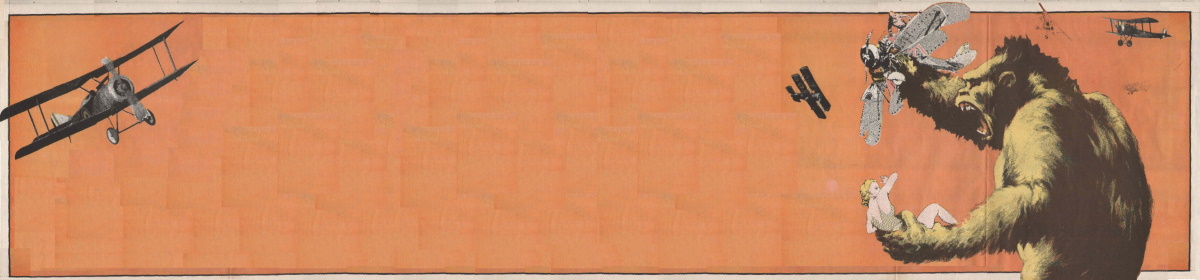

I WANT YOU TO BUY THIS GORILLA

BY STEVE VERTLIEB

THE MEN WHO SAVED KONG, PART 2

In our first issue, author Steve Vertlieb told us of THE MEN WHO SAVED KING KONG! In this second installment of the Kronicals of Kong, Steve shows us little-known facets of the most amazing of gems, the 20th-Century motion picture ad campaign. Ad promo is a fine science, and almost as creative and expensive as the movie itself. Sometimes more so, if a pretty bad movie is being pumped into the American public’s minds.

So, in HOW TO SELL A GORILLA, Steve tells us some interesting sidelights that make us drool with envy, wishing we could go back to that wonderful year, 1933, Great Depression notwithstanding, and watch how some of the largest cities in America went Kong-Krazy. But since we can’t, Steve’s article must serve as a time machine.

First Stop, ol’ Tinseltown itself Hollywood, California March 24th, 1933…..

“King Kong” had his Hollywood premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on Friday evening, March 24th, 1933. The souvenir-program book contained the following publicity blurb: “Out of an uncharted, forgotten corner of the world, a monster… surviving seven million years of evolution … crashes into the haunts of civilization… onto the talking screen … to stagger the imagination of man.” Mystery magazine celebrated the event by beginning a serialization of the story in their February, 1933 issue. Bruce Cabot and Fay Wray were on the cover, and the cover blurb billed the tale as “The last and the greatest creation of Edgar Wallace.”

On opening night in Hollywood the Premiere jitters were building and managed to leave practically no one untouched. But this night was not the beginning of the suspense, only the climax, for rumors had been circulating for months as to who and what King Kong was to be. R.K.O. Radio Pictures purchased one of the longest commercials in advertising history when, on February tenth, 1933, the National Broadcasting Company aired a thirty-minute radio program to let America know of the impending birth of King Kong. It was a show within a show, a sort of coming attraction, complete with specially tailored script and realistic sound effects. Reaction to the broadcast was exactly as hoped for – merely tremendous!

Original publicity releases and newspaper ads gave out verbal previews of what was to come: “Monsters Of Creation’s Dawn Break Loose In Our World Today” … “Never before had human eyes beheld an ape the size of a battleship” … “They saw the flying lizard, the fierce brontosaurus, big as twenty elephants… and all the living, fighting creatures of the infant world.” … “The giant ape leaped at the throat of the dinosaur and the death fight was on. A frightened girl, in 1933, witnessed the most amazing combat since the world began.”

Trailers (Coming Attractions) at the time, normally accustomed to previewing the most exciting scenes in a picture in order to entice a given audience, were deliberately secretive and noncommittal. Only a huge, frightening shadow was seen by theatre goers, accompanied by warnings like “This is only the shadow of King Kong … See the greatest sight that your eyes have ever beheld at this theatre – beginning Sunday!”

for one night only the KING KONG Ballet!

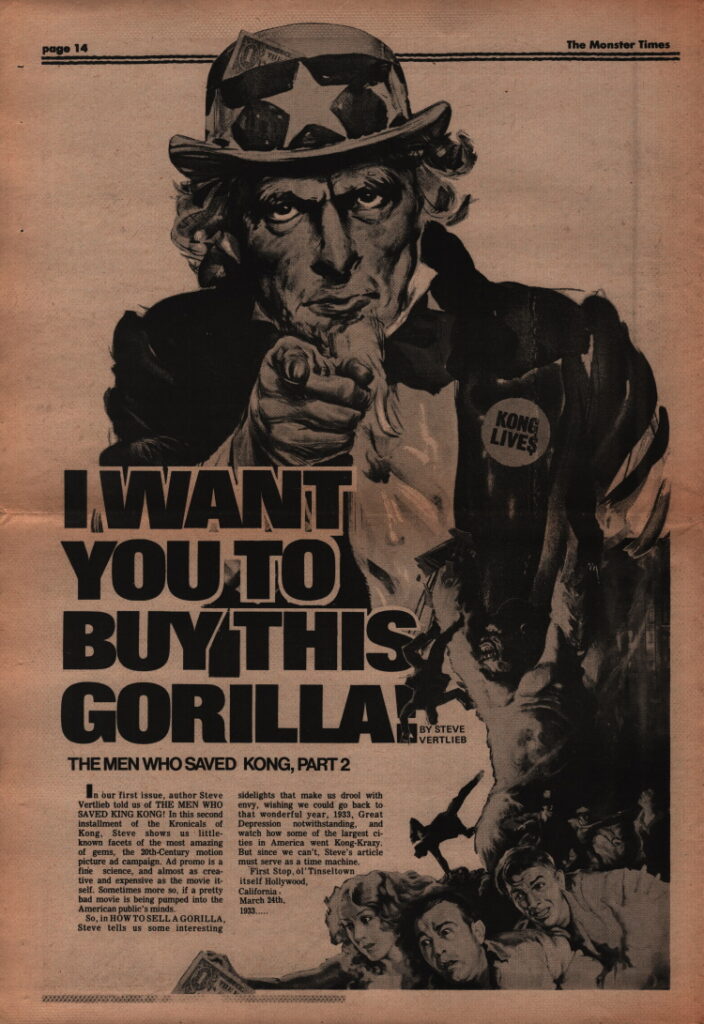

Sid Grauman was a showman and had earned his reputation from years of inventive staging. On this night of all nights he wasn’t going to be caught with his curtains down. Grauman arranged for a very special seventeen act extravaganza to precede the first showing of “King Kong.” He hired dancers, singers and musicians for the gala evening. To be sure, it was a night that no one who was there would ever forget. Recreated in these pages is the original program produced for that memorable evening thirty-eight years ago. Outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, that opening night was a life-size replica of Kong’s head! Kneat!

Finally, the moment that the huge audience in Hollywood had waited for was at hand. The house lights dimmed, the projectionist started his machine and a hush fell over the crowd. On-screen, the mammoth Radio Pictures tower beeped excitedly atop a spinning globe. It faded out and into a Radio Pictures Presents plaque. Finally, the logo faded out and onto the waiting screen came the title, in great block lettering, “KING KONG.” And, did it come? From the background, the title suddenly zoomed upfront to take its rightful place, prominently, in the foreground. It might almost have been an early form of 3-D!

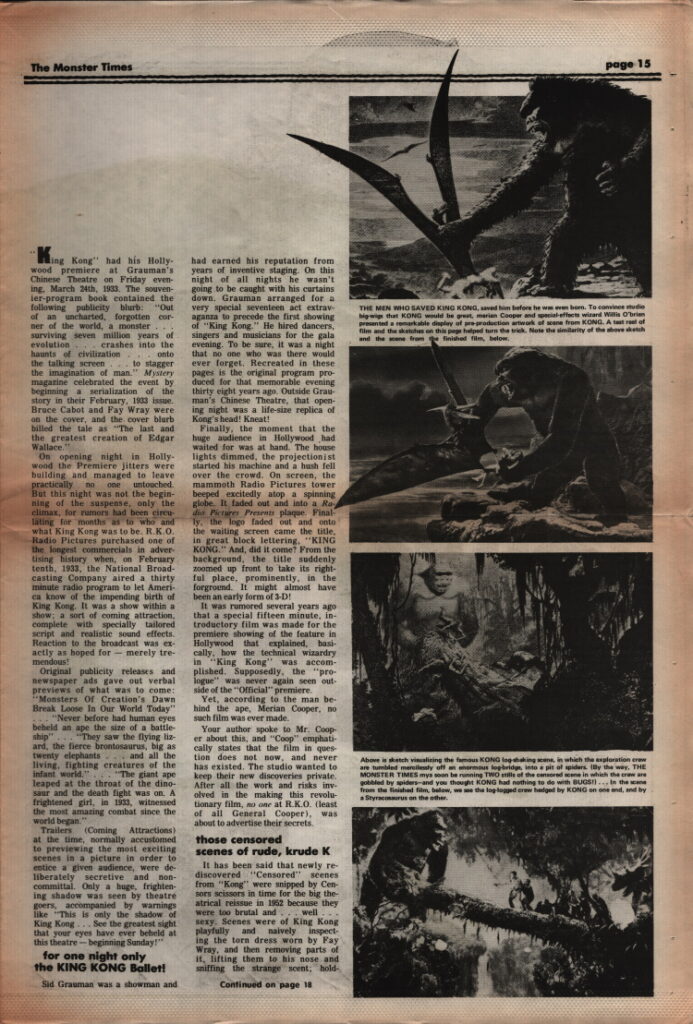

It was rumored several years ago that a special fifteen-minute, introductory film was made for the premiere showing of the feature in Hollywood that explained, basically, how the technical wizardry in “King Kong” was accomplished. Supposedly, the “prologue” was never again seen outside of the Official” premiere.

Yet, according to the man behind the ape, Merian Cooper, no such film was ever made.

Your author spoke to Mr. Cooper about this, and “Coop” emphatically states that the film in question does not now, and never has existed. The studio wanted to keep their new discoveries private. After all the work and risks involved in the making this revolutionary film, no one at R.K.O. (least of all General Cooper), was about to advertise their secrets.

those censored scenes of rude, krude K

It has been said that newly rediscovered “Censored” scenes from “Kong” were snipped by Censors scissors in time for the big theatrical reissue in 1952 because they were too brutal and … well … sexy. Scenes were of King Kong playfully and naively inspecting the torn dress worn by Fay Wray, and then removing parts of it, lifting them to his nose and sniffing the strange scent; holding a villager between his teeth; smashing down violently a structure upon which natives were standing and hurling spears; grinding the head of a writhing native into the mud on the ground with his foot; climbing the outer wall of a New York hotel at which Ann Darrow (Fay Wray) was staying, in search of his captive at large, and finding the first woman he sees asleep in her bed, then drawing her to him out through the window, examining her in mid-air and, realizing that he has picked the wrong girl, callously allowing her to slip through his fingers and fall to the ground below; and, lastly, chewing casually on a native New Yorker. It’s surprising he didn’t break his teeth!

It may now be wondered, however, if those sequences weren’t actually discarded in 1933 after the first run engagements, and when the film went into general release, for the recorded “running time” listed in the original studio Press Book is one hundred minutes – some five minutes less than the film would last with the additional “Censored” scenes left intact. In 1952 it was still 100 minutes.

As big and exciting as the Hollywood premiere was, “King Kong” really gave its world premiere some three weeks earlier to the city that graciously destroyed itself for movie history. It was fitting and proper that New York City host the unveiling of Carl Denham’s Monster, King Kong, the eighth wonder of the world!

And so it was that on March 2nd, 1933, “King Kong” created almost as much chaos for real as he did in the film. This was no ordinary premiere for, so great was the demand to see the new film that, in the midst of America’s worst and most tragic Depression, two enormous theatres were required to play the film simultaneously in order to fill the public’s demand for seats. Both the Radio City Music Hall and The Roxy Theatre, with a combined seating capacity of ten thousand people, were filled for every performance of the film from the moment when the doors opened at ten-thirty A.M. on Thursday, March 2nd. Both theatres took out combined ads in The New York Times the day preceding the opening. Kong, himself, was pictured atop the Empire State Building holding Fay Wray in one paw, and crushing a bi-plane in the other. The caption next to the ape and atop the title read:

“KONG THE MONSTER!”

Huge as a skyscraper … crashes into our city! See him wreck man’s proudest works while millions flee in horror! … See him atop the Empire State Tower! Battling planes for the woman in his ponderous paw! “KING KONG” outleaps the maddest imagination!”

As in Hollywood there were stage shows here also. “Stage Shows As Amazing As These Mighty Theatres,” proclaimed the advertisement. “Jungle Rhythms” – brilliant musical production! Entire singing and dancing ensemble of Music Hall and New Roxy! Spectacular dance rhythms by ballet corps and Roxyettes! Soloists, Chorus, Symphony, Orchestras, Company of 500!” “Big enough for the Two Greatest Theatres at the same time!”

“Kong” played to standing crowds for ten complete performances daily. On the day of the opening a second Ad appeared in New York’s entertainment pages. The publicity blurbs read, in part, “Shuddering terror grips a city … Shrieks of fleeing millions rise to the ears of a towering monster. .. Kong, king of an ancient world, comes to destroy our world – all but that soft, white female thing he holds like a fluttering bird … The arch-wonder of modern times.”

When, in 1933, President Roosevelt declared a Moratorium and closed the banks, the following Ad appeared in New York’s papers: “No Money … yet New York dug up $89,931.00 in four days (March 2, 3, 4, 5) to see “KING KONG” at Radio City setting a new all-time world’s record for attendance of any indoor attraction. This is all the more startling considering that general admission prices were far less expensive (10c to 50c) than they are today.

Full-page ads in the trade journals were headed by the impressive lead-in, “The Answer To Every Showman’s Prayer.” And it was. This was no case of attempting to sell a loser, for “Kong” was truly a box office bonanza for all film exhibitors sharing in the feast.

how to spread a gorilla-pic thin

Fay Wray’s awesome scream is equaled in its popularity only by Johnny Weismueller’s well-known cry as Tarzan, The Ape Man. No one has ever attempted a guess at why Fay’s screaming should have so completely overshadowed the tries of all other actresses throughout the thirty-eight years since “Kong”’s first release but few would doubt her right to the title of the world’s most celebrated screamer. So, it is not surprising to learn that R.K.O. used that contract scream in the voices of countless other actresses who were not as healthily endowed. When Helen Mack opened her fragile lips to cry out in “The Son Of Kong” it was not her voice audiences heard but that of Fay Wray. As late as 1945 Fay’s scream could be heard for Audrey Long in the remake of “The Most Dangerous Game,” “Game Of Death.”

But, of all of the memorable sounds to come from “King Kong,” the immortal music score by Max Steiner has been heard the most. “Kong”’s thrilling and intricate themes have been played in such later films as “The Son Of Kong,” “The Last Days Of Pompeii,” “Becky Sharpe,” (the first FULL Technicolor feature) “The Last Of The Mohicans,” “The Soldier And The Lady,” (from Jules Verne’s “Michael Strogoff”) and John Wayne’s “Back To Bataan.”

Sets and props used in “Kong” also had ways of turning up before the cameras of other pictures. The huge log that Kong hurled furiously into the spider pit was seen in the very same jungle in “The Most Dangerous Game.”

The doors that Cooper had built into the heart of DeMille’s Roman wall were transposed two years later from the tropical heat of Skull Island in the East Indies to the Artic wastelands for duty in the second filmed version of H. Rider Haggard’s classic fantasy, “SHE.”

“Kong,” unlike many other elder film favorites seems to grow in stature with the passing years and is more cherished today than when it was first released back in the midst of the depression. At the box office “King Kong” grew more financially rewarding with every new release and must come second to “Gone With The Wind” in its number of new re-releases. It continued to come back to first-run theatres in 1938, 1942, 1947, 1952, 1956 and finally in 1970 for a limited engagement at “Art Theatres” across the country. Today’s film fans and critics have begun noticing all manner of subtle sophistications that totally escaped the more naive film-goers of the thirties.

the Merian who saved KING KONG

In 1932 the cast and crew of “King Kong” sent a Christmas card to Merian Coldwell Cooper that portrayed him, in caricature, shouting “Make it bigger. Make it big – ger.” Well, the prophecy was realized and Coop got his wish. Carl Denham, a thinly disguised replica of Cooper himself, said on the eve of their coming adventure, “I’m going out and make the greatest picture in the world, something that nobody’s ever seen or heard of. They’ll have to think up a lot of new adjectives when I come back!” Denham kept his word, and. so did Cooper. He gave the world the finest, best-loved and remembered fantasy in the history of Motion Pictures. And they did have to think up a lot of new adjectives when he came back.

Were it not for Cooper and his deeply rooted faith in “Kong” the movie might never have been made. .. or, worse, it would have been made without its gifted creator continually at the helm. Without his belief in the possibilities of animator Willis O’Brien’s Stop Motion; his insistence that Max Steiner create an original music score for the film when the “Money Men” were against the idea; his feeling for authentic, far off adventure, “Kong” would have turned out a different film indeed and, quite probably, would be long forgotten by this time.

However, Merian C. Cooper was very much behind the making of the movie and he, more than Willis O’Brien and Max Steiner, was responsible for saving” KING KONG.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Max Steiner, composer of the shuddering music of KING KONG, has died. His obituary is on MT Teletype, page 11.