By JOE KANE

Hey Gang!

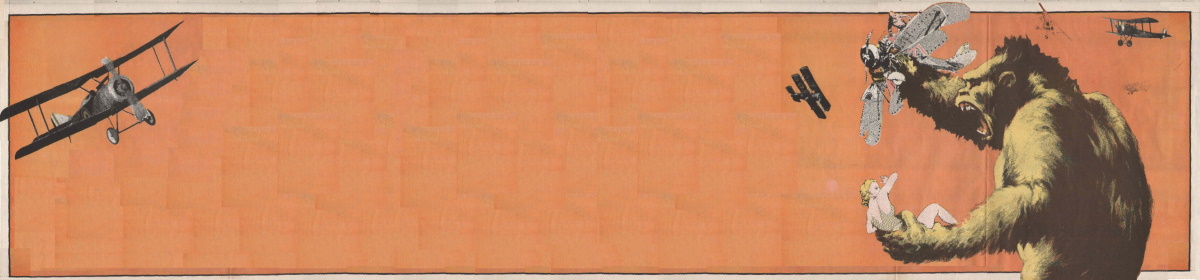

Remember the Atomic Bomb? Recollect the ol’ Hydrogen Bomb? And the “A” Bomb that gave birth to RODAN and GODZILLA? The “H” bomb that caused THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN to dwindle to nothingness? And the Bomb that made the AMAZING COLOSSAL MAN grow to a height of 50 feet?

Remember the invention that transformed a man of flesh and blood into a superman of steel, making him THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN ALIVE? And what about the “scientific breakthrough” that unleashed a race of THEM giant ants, to swarm, spreading death and destruction across the American Desert? And of course the doomsday devices that invited strange messengers from dim, distant planets, scurrying like concerned tourists to our little old Earth to warn mankind of its Dangerous New Powers? And you surely remember the many times the Bomb reduced our bustling, happy world to a vast wasteland of radioactive ash. On film, anyway.

Well, we do! That’s why we’re going to take a trip down Memory Lane (the one that glowed mysteriously in the dark), noting nostalgically the Good Old Bad Days, when, on every lead-lined silver screen there popped up bumper crops of…

MUSHROOM MONSTERS or: The Day The World Ended & Ended…

Atomic Bomb. Hydrogen Bomb. Radioactive Fallout. Fallout Shelter. Overkill. These were only a few of the new and peculiar terms that were ushered in by the advent of nuclear energy and the atomic bomb to dwarf the befuddled human mind. And there was a good reason for this fear, for the terrible carnage that the Atom Bomb could wreak on people and property had already been demonstrated in 1945 in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, at the expense of some 150,000 lives and countless other victims who would bear the drastic and permanent scars of nuclear abuse.

As the nuclear arms race between the United States and Russia got fully underway in the Fearful Fifties, these terms grew to take on increasingly powerful and terrifying meaning as people throughout the world began to realize that they were living under the frightening shadow of instant and total destruction. A terrible equality had been born.

Filmmakers were quick to pick up on the theme of The Bomb and its awesome potential for human contamination and world annihilation. They, like the general population, were less interested in the positive use of nuclear energy because its capacity for damage was so overwhelming and, in a human sense, limitless, that the fears and guilt its presence inspired had to be dealt with first. Film audiences were simultaneously repulsed and fascinated by The Bomb. And there were chilling questions they wanted answered-that had to be answered, or at least explored-even if only by the Hollywood imagination.

And there were many questions indeed:

What could the Bomb do to people?

What unimaginable mutations would take place in the human body, mind, and spirit?

What terrible distortions of Nature would result?

What kind of world would be left after a nuclear world war?

Would there be any survivors at all?

If so, would mankind revert to a primitive, prehistoric way of life, foraging for animal survival in a worldwide primal jungle?

The filmmakers, like the science-fiction writers in the literary world, assigned themselves the task of offering possible answers to those questions posed by the impolite presence of The Bomb. Between 1950 and 1965, scores of movies dealing in one way or another with the deadly presence of nuclear energy mushroomed on the screen. Generally they concentrated on the theme of the human misuse of this potent but morally neutral force.

Four general types of film emerged: (1) the Human-Mutation film, (2) the Return of the Prehistoric Beast film, (3) the Post-World Destruction film, and (4) the Warning From Space film.

Each of these four film categories and the monsters each produced, will be discussed in four separate articles in four future issues of THE MONSTER TIMES.

Horrible mutations, the re-awakening of dinosaurs and other early monsters, atomically-induced disasters, and unearthly visitors with messages of doom-all brands of nuclear nightmare flooded the American movie screen during this period. Ironically enough, the only other country to really explore the dangers of nuclear abuse in film was Japan-the only actual victim of the Bomb’s wrath. The Russians, who were working night and day to build an atomic arsenal that can destroy the world merely 60 times over (as compared with our 100 times over) oddly found nothing of entertainment value in their much-tested but untried new toys. They just didn’t join in the fun.

One of the first films that set out to depict the effects of nuclear war was Arch Oboler’s Five, released in 1950. Oboler, who had already developed a reputation in the world of science-fiction and horror through his famous spell-binding Lights Out! radio broadcasts in the 30’s and 40’s (considered second only to Orson Welles’ legendary hysteria-inspiring broadcast of War of the Worlds), occasionally turned to film as a medium for his many talents, directing Bewitched (1945), The Twonky, the tale of a walking, talking TV-set like an antennae’d invader from space (1953), and a 3-D effort, Bwana Devil (1952.)

Five was a deeply felt, highly personal project that set the tone for many later films on this subject. His image of the scarred wastelands of an atomically-demolished earth are among the most haunting ever to reach the screen. Arch Oboler’s story is a simple and basic one: After the nuclear transformation of Earth from a busy, hectic planet crammed with war and emotional conflict into the silent death scape it becomes in Five, only five people are left alive to recreate in miniature the kind of human in-fighting and self-destructive urges that led to a nuclear war in the first place.

The steady disintegration of the desperate survivors mirrors the problems people have in getting along, even when they have a common goal to achieve. At the end of the film only two remain-a post-holocaust Adam & Eve determined to begin the species anew. Good Luck!

Although Five would be placed, in the third category of the nuclear film-the Post-World Destruction film-I mention it now because it is really the first to tackle the dangers of The Bomb head-on. While its basic plot and characterizations were not earth-shakingly original, Five’s compelling images of sheer desolation and total world desertion were something new.

The most terrifying aspect of Oboler’s Five was that it was not an outlandish or smirky science-fiction fantasy in which the world was destroyed by interplanetary warfare, or divine biblical floods, or secret creatures rascally sneaking up from the bowels of the earth. On the contrary, it was done by man, and man alone. It represented a vast mass suicide, a self-destructive plot that involved everyone-no matter who the aggressors might be; everyone, including the aggressors, were victims. There was no one else to blame. This represented a drastic departure and increased the psychological horror a hundredfold.

Of course, the idea was not enough; it required talent and imagination to really bring it off. And Oboler had it.

The most common theme explored by Hollywood filmmakers was of human beings turned into monsters and outcasts as a result of nuclear contamination.

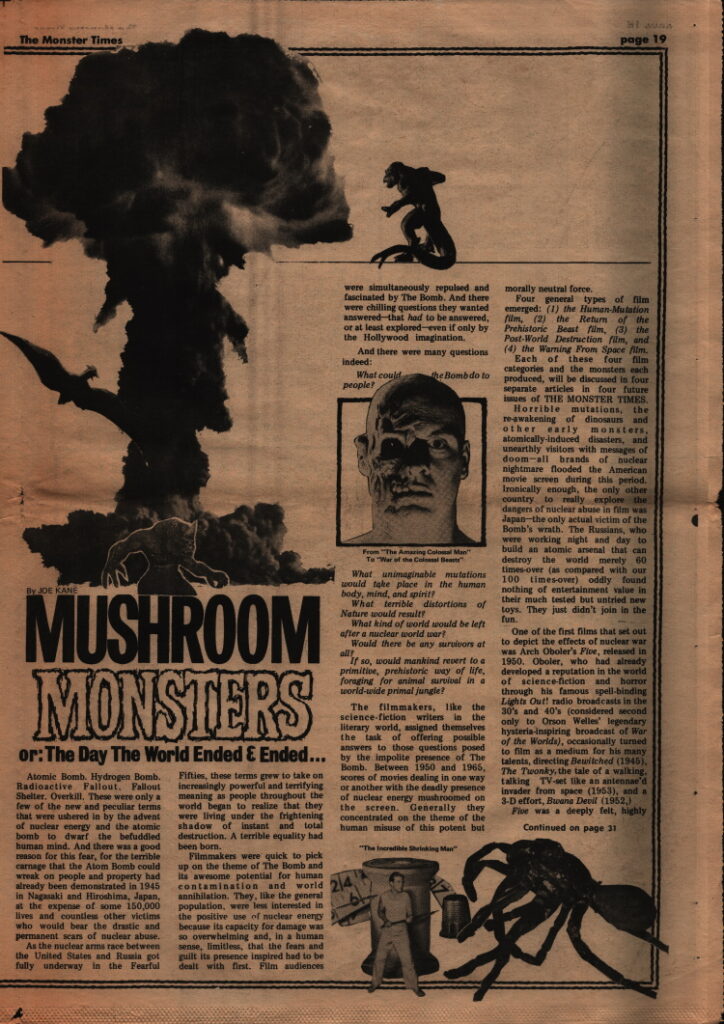

A typical human-mutation film is the AMAZING COLOSSAL MAN, released by the prolific (if not always brilliant) AmericanInternational studio. In this film an army officer (Glenn Langan) becomes infected by radioactive particles that renew the growth process. As he grows, his distance from his fellow humans takes on vast emotional as well as physical dimensions.

He knows he is viewed by others as a freak and the efforts of the American Lilliputians to help him become increasingly incomprehensible to him. His mind gradually drifts into a state of child-like confusion, and he begins to lash out at the hordes of miniature human pests who trail and torment him. The distinction between friend and foe disappears from his mind and soon enough ALL become the enemy as he takes out his mammoth frustrations on a Las Vegas toyland.

Of course, he is then destroyed-shot by a bazooka and then falls into the Grand Coulee Dam, no less-only to return, marred and scarred, in an inept sequel called THE WAR OF THE COLOSSAL BEAST, having apparently made the final transition from ‘man’ to ‘beast.’ At least in the title, anyway, the producers really made the transformation.

One of the earliest (and best) Warning From Space films is THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL, in which Michael Rennie plays a visitor from the vast intergalactic beyond, who comes to warn this wicked world not to play with nuclear fire and to request an end to ALL manner of warfare. This film stood out as one of the best of its period, in the horror-sci-fi genre, and we’ll be taking a closer look at it in a future installment in this series. (As well as presenting a special Encyclopedia Filmfannica treatment soon-Editor)

Most of the mutation films lacked the drive and imagination to really make the horror aspect work, but a few classics did emerge. For every few films that were content to spring a make-up man’s monster on an undemanding audience, there was one that went beyond, to probe the possible terrors of human contamination. One of the best of these mutation films, The Incredible Shrinking Man, will be discussed, along with several others, in the next issue of MT.

Stay tuned… and try to keep from glowing in the dark! It’s not polite.